How much timing do you need? PTP can get you timing in the nanoseconds, but is that needed, how can you transport it and how does it work? These questions and more are under the microscope in this video from RTS Thames Valley.

SMPTE Standards Vice President, Bruce Devlin introduces the two main speakers by reminding us why we need timing and how we dealt with it in the past. Looking back to the genesis of television, points out Bruce, everything was analogue and it was almost impossible to delay a signal at all. An 8cm, tightly wound coil of copper would give you only 450 nanoseconds of delay alternatively quartz crystals could be used to create delays. In the analogue world, these delays were used to time signals and since little could be delayed, only small adjustments were necessary. Bruce’s point is that we’ve swapped around now. Delays are everywhere because IP signals need to be buffered at every interface. It’s easy to find buffers that you didn’t know about and even small ones really add up. Whereas analogue TV got us from camera to TV within microseconds, it’s now a struggle to get below two seconds.

Hand in hand with this change is the change from metadata and control data being embedded in the video signal – and hence synchronised with the video signal – to all data being sent separately. This is where PTP, Precision Time Protocol, comes in. An IP-based timing mechanism that can keep time despite the buffers and allow signals to be synchronised.

Next to speak is Richard Hoptroff whose company works with broadcasters and financial services to provide accurate time derived from 4 satellite services (GPS, GLONASS etc) and the Swedish time authority RiSE. They have been working on the problem of delivering time to people who can’t put up antennas either because they are operating in an AWS datacentre or broadcasting from an underground car park. Delivering time by a wired network, Richard points out, is much more practical as it’s not susceptible to jamming and spoofing, unlike GPS.

Richard outlines SMPTE’s ST 2059-2 standard which says that a local system should maintain accuracy to within 1 microsecond. the JT-NM TR1001-1 specification calls for a maximum of 100ms between facilities, however Richard points out that, in practice, 1ms or even 10 microseconds is highly desired. And in tests, he shows that with layer 2, PTP unicast looping around western Europe was able to adhere to 1 microsecond, layer 3 within 10 microseconds. Over the internet, with a VPN Richard says he’s seen around 40 microseconds which would then feed into a boundary clock at the receiving site.

Summing up Richard points out that delivering PTP over a wired network can deliver great timing without needing timing hardware on an OPEX budget. On top of that, you can use it to add resilience to any existing GPS timing.

Gerard Philips from Arista speaks next to explain some of the basics about how PTP works. If you are interested in digging deeper, please check out this talk on PTP from Arista’s Robert Welch.

Already in use by many industries including finance, power and telecoms, PTP is base on IEEE-1588 allowing synchronisation down to 10s of nanoseconds. Just sending out a timestamp to the network would be a problem because jitter is inherent in networks; it’s part and parcel of how switches work. Dealing with the timing variations as smaller packets wait for larger packets to get out of the way is part of the job of PTP.

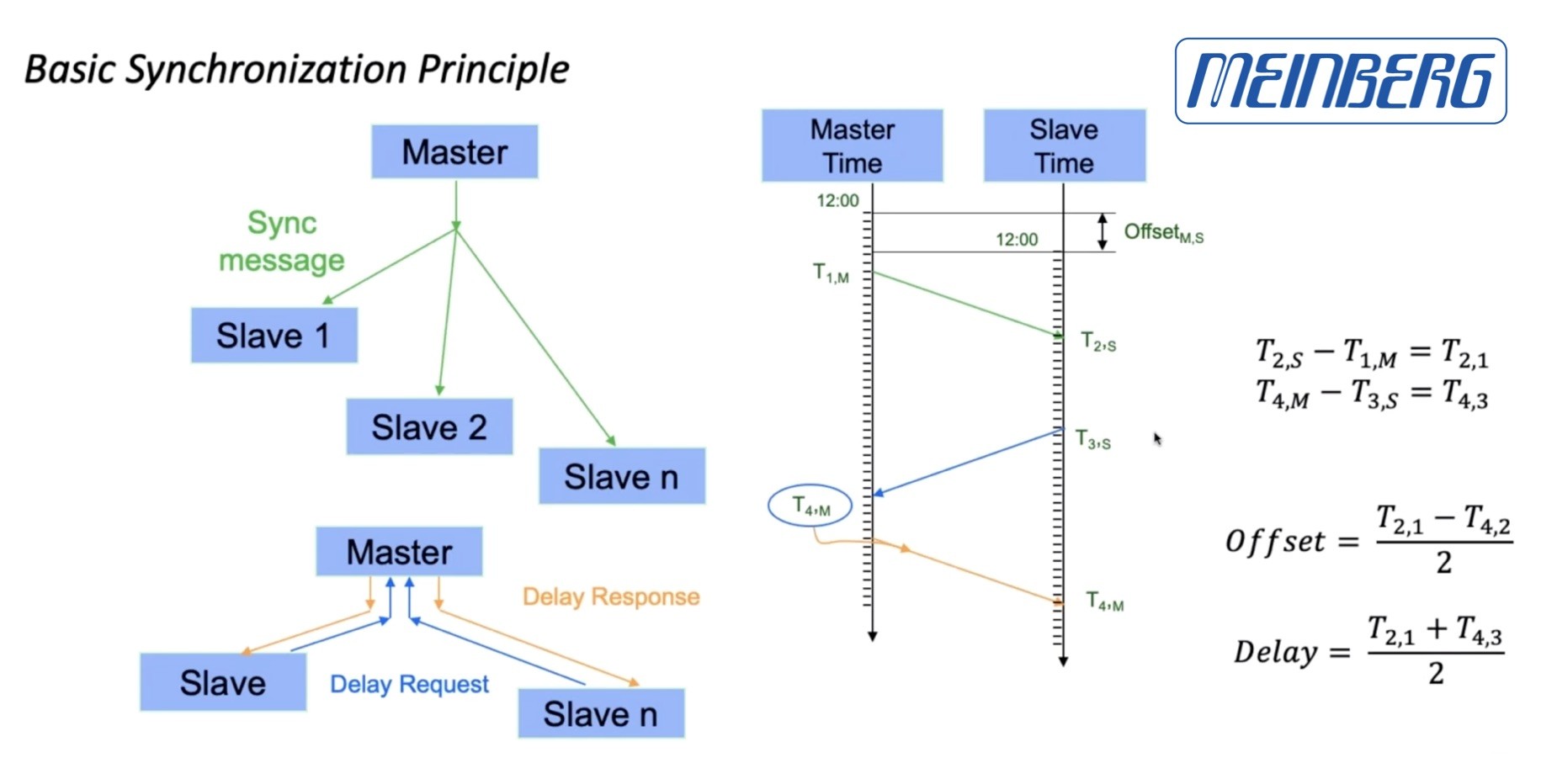

To do this, the main clock – called the grandmaster – sends out the time to everyone 8 times a second. This means that all the devices on the network, known as endpoints, will know what time it was when the message was sent. They still won’t know the actual time because they don’t know how long the message took to get to them. To determine this, each endpoint has to send a message back to the grandmaster. This is called a delay request. All that happens here is that the grandmaster replies with the time it received the message.

PTP Primary-Secondary Message Exchange.

Source: Meinberg [link]

This gives us 4 points in time. The first (t1) is when the grandmaster sent out the first message. The second (t2) is when the device received it. t3 is when the endpoint sent out its delay request and t4 is the time when the master clock received that request. The difference between t2 and t1 indicates how long the original message took to get there. Similarly, t4-t3 gives that information in the other direction. These can be combined to derive the time. For more info either check out Arista’s talk on the topic or this talk from RAVENNA and Meinberg from which the figure above comes.

Gerard briefly gives an overview of Boundary Clock which act as secondary time sources taking pressure off the main grandmaster(s) so they don’t have to deal with thousands of delay requests, but they also solve a problem with jitter of signals being passed through switches as it’s usually the switch itself which is the boundary clock. Alternatively, Transparent Clock switches simply pass on the PTP messages but they update the timestamps to take account of how long the message took to travel through the switch. Gerard recommends only using one type in a single system.

Referring back to Bruce’s opening, Gerard highlights the need to monitor the PTP system. Black and burst timing didn’t need monitoring. As long as the main clock was happy, the DA’s downstream just did their job and on occasion needed replacing. PTP is a system with bidirectional communication and it changes depending on network conditions. Gerard makes a plea to build a monitoring system as part of your solution to provide visibility into how it’s working because as soon as there’s a problem with PTP, there could quickly be major problems. Network switches themselves can provide a lot of telemetry on this showing you delay values and allowing you to see grandmaster changes.

Gerard’s ‘Lessons Learnt’ list features locking down PTP so only a few ports are actually allowed to provide time information to the network, dealing carefully with audio protocols like Dante which need PTP version 1 domains, and making sure all switches are PTP-aware.

The video finishes with Q&A after a quick summary of SMPTE RP 2059-15 which is aiming to standardise telemetry reporting on PTP and associated information. Questions from the audience include asking how easy it is to do inter-continental PTP, whether the internet is prone to asymmetrical paths and how to deal with PTP in the cloud.

Watch now!

Speakers

|

Bruce Devlin Standards Vice President, SMPTE |

|

Gerard Phillips Systems Engineer, Arista |

|

Richard Hoptroff Founder and CTO Hoptroff London Ltd |