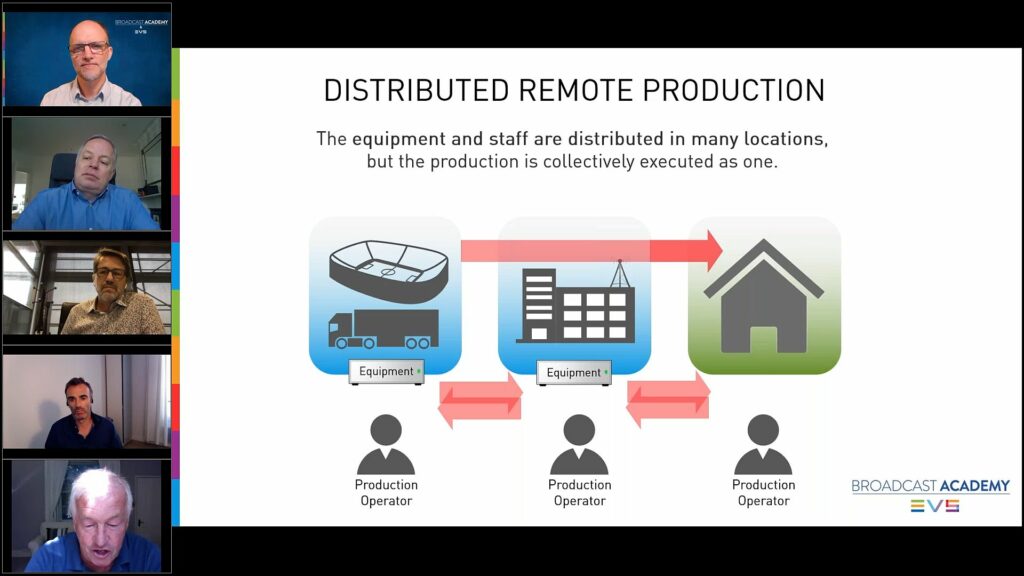

Remote production is changing. Gone are the days when it meant leaving some of your team at base instead of sending them with the football OB. Now it can mean centralised remote production where, as Eurosport has recently shown, TV stations around Europe can remotely use equipment hosted in two private cloud locations. With the pandemic, it’s also started to mean distributed remote production, where the people are now no longer together. This follows the remote production industry’s trend of moving the data all into one place and then moving the processing to the media. This means public or private clouds now hold your files or, in the case of live production like Eurosport, the media and the processing lives there too. It’s up to you whether you then monitor that in centralised MCR-style locations using multiviewers or with many people at home.

This webinar hosted by EVS in association with the Broadcast Academy which is an organisation started by HBS with the aim of creating cosntency of live production throughout the industry by helping people build their skillsets ensuring the inclusion of minorities. With moderator James Stellpflug from EVS is Gordon Castle from Eurosport, Mediapro’s Emili Planas, producer & director John Watts and Adobe’s Frederic Rolland.

Gordon Castle starts and talks with the background of Eurosport’s move to a centralised all-IP infrastructure where they have adopted SMPTE ST 2110 and associated technologies putting all their equipment in two data centres in Europe to create a private cloud. This allows producers in Germany, Finland, Italy and at least 10 other markets to go to their office as normal, but produce a program using the same equipment pool that everyone else uses. This allows Eurosport to maximise their use of the equipment and reduce time lying idle. It’s this centralised remote production model which feeds into Gordon’s comment about wanting to produce more material at a higher quality. This is something that he feels has been achievable by the move to centralisation along with giving more flexibility for people on their location.

Much of the conversation revolved around the pandemic which has been the number one forcing factor in the rise of decentralised remote production seen over the last two years where the workforce is decentralised, often with the equipment centralised in a private or public cloud. The consensus in the panel is that the move to home working is often beneficial, but splitting up the team is a problem in the long term. A team that has worked together for a long time can survive on this is previously gained knowledge of how people work, their benefits and relationships forged in the heat of broadcast and over the dinner table. Bringing together a new team without close interpersonal contact raises the risk of transactional behaviour, not working as a team or simply not understanding how other people work. A strong point made is that an OB is like a sports team on the pitch. The players know where they are supposed to be, their role and what they are not supposed to do. They look out for each other and can predict what their teammates will want or will do. We see this behaviour all the time in galleries around the world as people produce live events, but the knowledge that rests on as well as the verbal and visual cues needed to make that work can be absent if the team has always worked remotely.

Economics plays a role in promoting remote production within companies. For Gordon, there’s a cost benefit in not having OBs on site although he does acknowledge that depending on the country and size of the OB there are times when an on-site presence is still cheaper. When you don’t have all staff on site, people are more available for other work meaning they can do multiple events a day, though John Watts cautions that two football matches are enough for one director if they want to keep their ‘edge’. The panel share a couple of examples about how they are keeping engagement between presenters despite not being in the same place, for instance, Eurosport’s The Cube.

On technical matters, the panel discusses the difficulty of ensuring connectivity to the home but is largely positive about the ability to maintain a working-from-home model for those who want it. There are certainly people whose home physically doesn’t accommodate work or whose surroundings with young family members, for instance, don’t match with the need to concentrate for several hours on a live production. These problems affect individuals and can be managed and discussed in small teams. For large events, the panel considers remote working much more difficult. The overhead for pulling together multiple, large teams of people working at home is high and whether this is realistic for events needing one hundred or more staff is a question yet to be answered.

As the video comes to a close, the panel also covers how software, one monolithic, is moving towards a federated ecosystem which allows broadcasters more flexibility and a greater opportunity to build a ‘best of breed’ system. It’s software that is unlocking the ability to work in the cloud and remotely, so it will be central to how the industry moves forward. They also cover remote editing, the use of AI/ML in the cloud to reduce repetitive tasks and the increased adoption of proxy files to protect high-quality content in the cloud but allow easy access and editing at home. 5G comes under discussion with much positivity about its lower latency and higher bandwidth for both contribution and distribution. And finally, there’s a discussion about the different ways of working preferred by younger members of the workforce who prefer computer screens to hardware surfaces.

Watch now!

Speakers

|

Emili Planas CTO and Operations Manager, Mediapro |

|

John Watts Executive Producer, Director & Broadcast Academy Expert |

|

Fréderic Rolland International Manager, Strategic Development, Video Business, Adobe |

|

Gordon Castle SVP Technology, Eurosport |

|

Moderator: James Stellpflug SVP Markets, EVS |