With the streaming market maturing, keeping ahead of competitors requires a layered strategy, particularly for entrants to the market who don’t have Amazon levels of funding. There are success stories out there, so what are the ingredients for success? This recored webinar looks at these questions an shares advice on succeeding in today’s market.

Rahul Patel from Ampere Analysis is first giving an overview of the OTT/streaming market. Within the UK and the US, we now see, he explains, 35% of subscriptions belonging to those 45 and older thus the market is maturing and increasingly offering a wider choice of genres to a wider selection of people. In general, services stand out through their content which is often done through original productions with Netflix now investing almost the same in original programming as the BBC does across all its channels. Rahul shows statistics showing that the percentage of non-US productions is increasing with Netflix and Amazon prime both trying to create programming which is more appealing to their non-US viewers.

An alternative to original programming is to focus your offering. For example, services such as AcornTV focus on UK crime drama, Crunchyroll is focussed on Japanese-made programming and Mubi is 100% films. Though in one market, a very narrow niche may not provide the customers needed to make the service viable, but expanded across all markets, that can all change. Another way services are attracting subscribers, Rahul details, is through bundling either with multiple services being discounted when purchased together, free subscription with hardware purchase or partnerships between big players such as network operators.

As the stacking of services continues to increase, Rahul foresees a future role for aggregators and simplifying the subscription to one payment. Aggregation would involve a single search interface unifying disparate services and could be provided by giants such as Apple and Amazon.

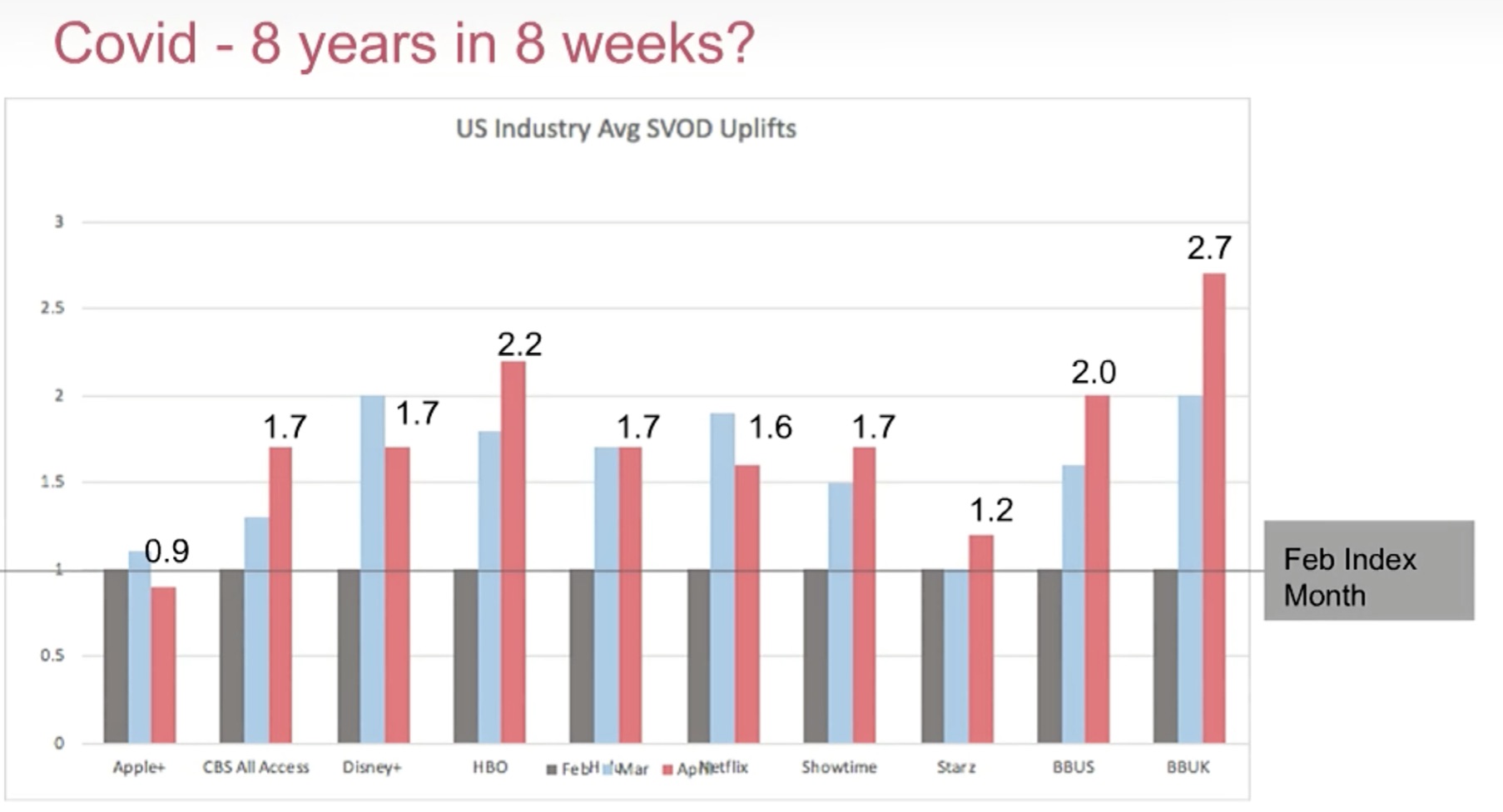

US Industry Avg SCOD Uplifts. Source Reemah Sakaan, BritBox

Next up is Reemah Sakaan from BritBox, which launched in the US in 2017, now in the UK as of 2019 and soon Australia. She explains their journey to market discussing how it can take long time to get rights and forge a true identity, but once that is done, an easy to understand offering can be quickly taken up by viewers. Reemah notes that Covid-19 has pushed a hugh change in viewership both in terms of viewing hours but also subscribers and underlined the importance of their embedded live feed which allows them to go live with special events such as the Royal Wedding along side the traditional VoD offering. This helps them be a unique service and maintain differentiation from competitors.

The last of the presentations is from Simon James from Applicaster. Applicaster’s focus is on providing apps for streaming services. Major issues are in scaling your app on all platforms and trying to manage testing across different OS types and versions. Simon says that the effort needed to keep up with all of this can sap energy and innovation from the team. It also makes it hard to be agile and respond to the market and viewers within the pandemic being a fantastic example of why.

The video ends with a Q&A covering increasing subscriber churn which may lead to annual discounts rather than a monthly subscription. Reemah explains that the first 100 days is key in keeping subscribers. Other questions cover the need for consistent user experience across platforms, approach to expansion and the applicability of your content to your viewers.

Watch now!

Speakers

|

Reemah Sakaan Group Director, SVOD at ITV Chief Brand and Creative Development Officer, BritBox Global |

|

Rahul Patel Analyst, Ampere Analysis |

|

Simon James Head of Sales Engineering, Applicaster |