How do we reconcile the tension between the continual move towards virtualisation, microservices and docker-like deployments and the requirements of SMPTE 2110 to have highly precise timing so it can synchronise the video, audio and other essence streams? Virtualisation adds fluidity in to computing so it can share a single set of resources amongst many virtual computers yet PTP, the Precision Time Protocol a successor to NTP, requires close to nano-second precision in its timestamps.

Alex Vainman from Mellanox explains how to make PTP work in these cases and brings along a case study to boot. Starting with a little overview and a glossary, Alex explains the parts of the virtual machine and the environment in which it sits. There’s the physical layer, the hypervisor as well as the virtual machines themselves – each virtual machine being it’s own self-contained computer sitting on a shared computer. Hardware must be shared between, often, many different computers. However some devices aren’t intended to be shared. Take, for instance, a dongle that contains a licence for software. This should clearly be only owned by one computer therefore there is a ‘direct’ mode which means that it is only seen by one computer. Alex goes on to explain the different virtualisation I/O modes which allow devices which can be shared, a printer, storage or CPU for instance need to have access computers may need to wait until they have access to the device to enable sharing. Waiting, of course, is not good for a precision time protocol.

In order to understand the impact that virtualisation might have, Alex details the accuracy and other requirements necessary to have PTP working well enough to support SMPTE 2110 workflows. Although PTP is an IEEE standard, this is just a standard to define how to establish accurate time. It doesn’t help us understand how to phase and bring together media signals without SMPTE ST 2059-1 and -2 which provide the standard of the incoming PTP signal and the way by which we can compare timing and media signals (more info here.) All important is to understand how PTP can actually determine the accurate time given that we know every single message has an unknown propagation delay. By exchanging messages, Alex shows, it is quite practical to measure the delays involved and bring them into the time calculation.

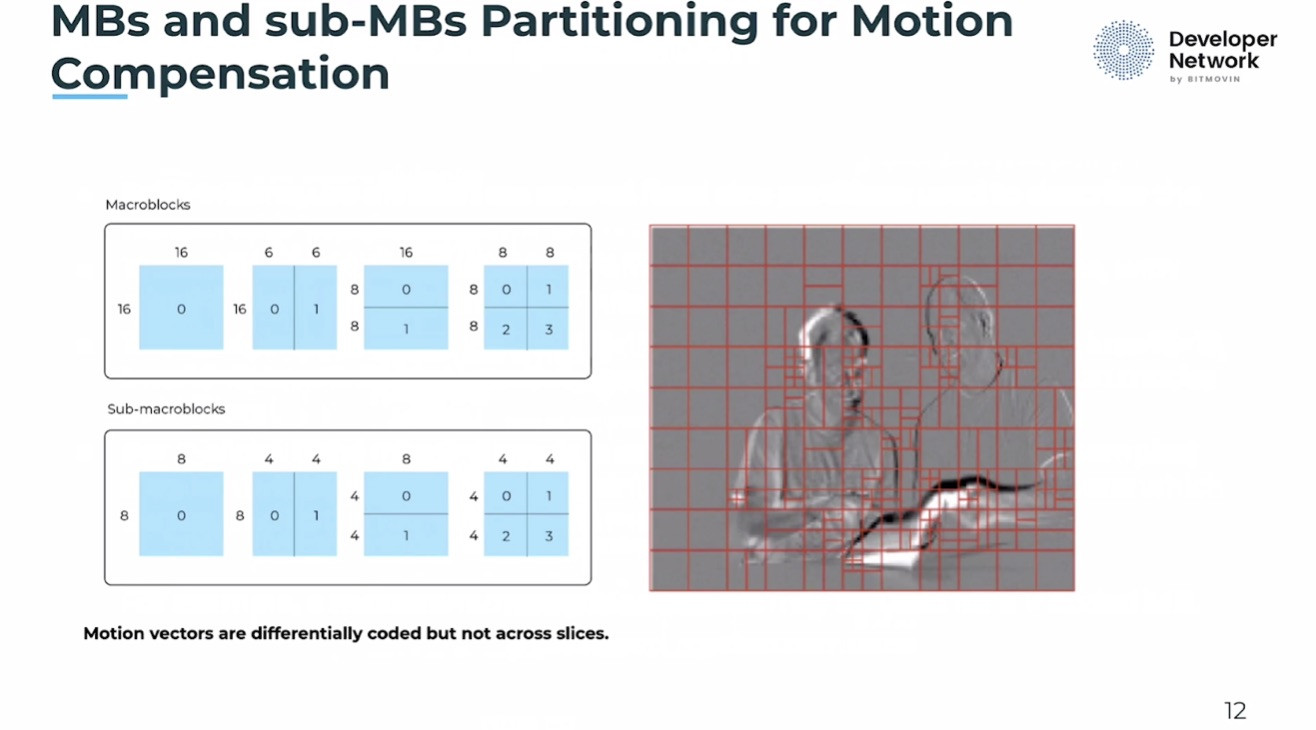

We now have enough information to see why the increased jitter of VM-based systems is going to cause a problem as there are non-deterministic factors such as contention and traffic load to consider as well as factors such as software overhead. Alex takes us through the different options of getting PTP well synchronised in a variety of different VM architectures. The first takes the host clock and ensures that is synchronised to PTP. Using a dedicated PTP library within the VM, this then speaks to the host clock and synchronises the VM OS clock providing very accurate timing. Another, where hardware support in the VM’s hardware for PTP isn’t present, is to have NICs with dedicated PTP support which can directly support the VM OSes maintaining their own PTP clock. The major downside here is that each OS will have to make their own PTP calls creating more load on the PTP system as opposed to the previous architecture whereby the host clock of the VM was the only clock synchronising to the system PTP and therefore there was only ever one set of PTP messages no matter how many VMs were being supported.

To finish off, Alex explains how Windows VMs can be supported – for now through third-party software – and summarises the ways in which we can, in fact, create PTP ecosystems that incorporate virtual machines.

Watch now!

Download the slides

Speakers

|

Alex Vainman Senior Staff Engineer, Mellanox Technologies |