Adding a new codec to your streaming service is a big decision. It seems inevitable that H.264 will be around for a long time and that new codecs won’t replace it, but just take their share of the market. In the short term, this means your streaming service may also need to deliver H.264 and your new codec which will add complexity and increase CDN storage requirements. What are the steps to justifying a move to a new codec and what’s the state of play today?

In this Streaming Media panel, Jan Ozer is joined by Facebook’s Colleen Henry, Amnon Cohen-Tidhar from Cloudinary and Anush Moorthy from Netflix talk about their experiences with new codecs and their approach to new Codecs. Anush starts by outlining the need to consider decoder support as a major step to rolling out a new codec. The topic of decoder support came up several times during this panel in discussing the merits of hardware versus software decoding. Colleen points out that running VP9 and VVC is possible, but some members of the panel see a benefit in deploying hardware – sometimes deploying on devices like smart TVs, hardware decoding is a must. When it comes to supporting third party devices, we hear that logging is vitally important since when you can’t get your hands on a device to test with, this is all you have to help improve the experience. It’s best, in Facebook’s view, to work closely with vendors to get the most out of their implementations. Amnon adds that his company is working hard to push forward improved reporting from browsers so they can better indicate their capabilities for decoding.

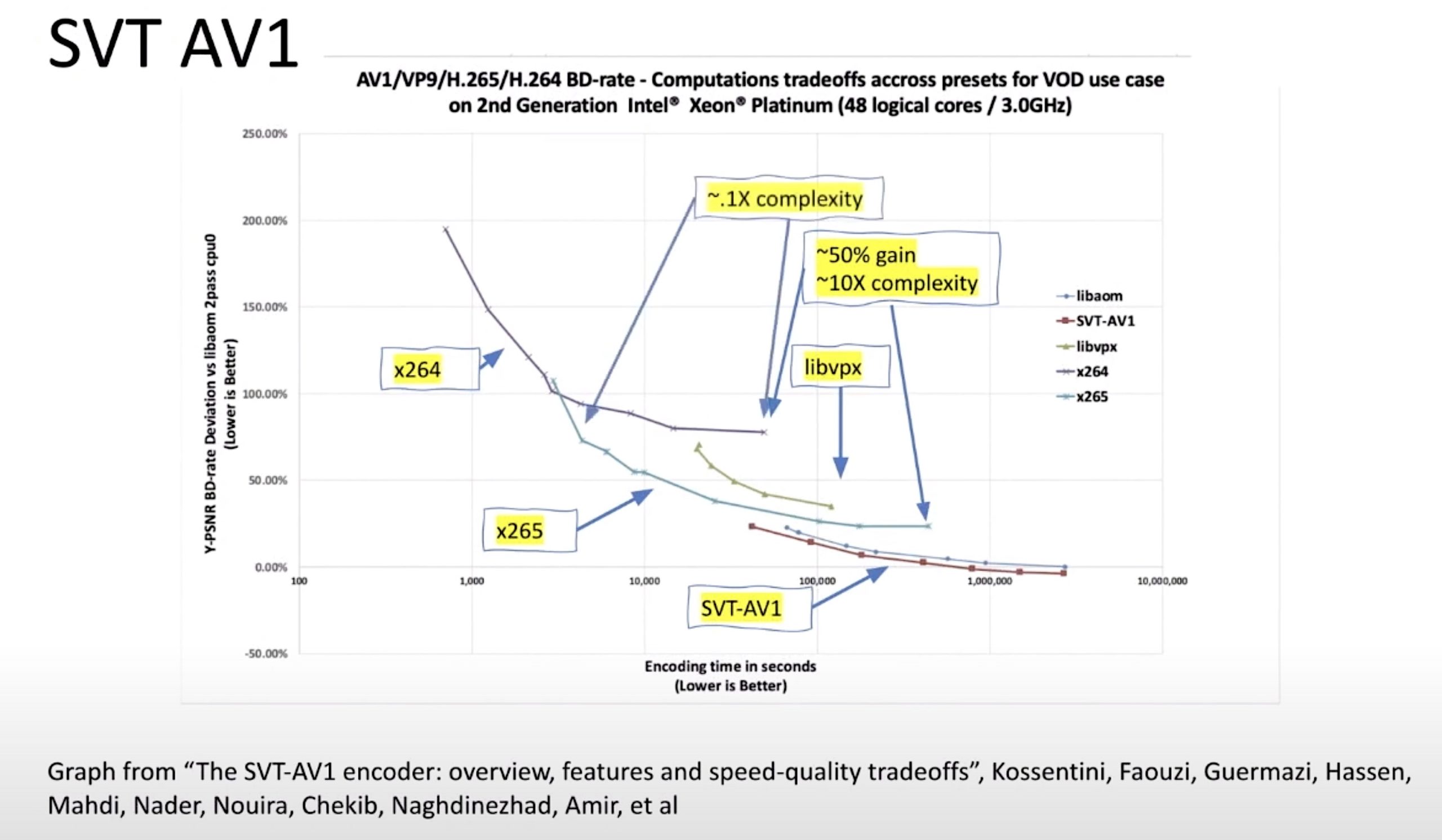

Colleen talks about the importance of codec switching to enhance performance at the bottom end of the ABR ladder with codecs like AV1 with H264 at the higher end. This is a good compromise between the computation needed for AV1 and giving the best quality at very low bitrates. But Anush points out that storage will increase when you start using two codecs, particularly in the CDN so this needs to be considered as part of the consideration of onboarding new codecs. Dropping AV1 support at higher bitrates is an acknowledgement that we also need to consider the cost of encoding in terms of computation.

The panel briefly discusses the newer codecs such as MPEG VVC and MPEG LCEVC. Colleen sees promise in VVC in as much as it can be decoded in software today. She also says good things about LCEVC suggesting we call it an enhancement codec due to the way it works. To find out more about these, check out this SMPTE talk. Both of these can be deployed as software decoders which allow for a way to get started while hardware establishes itself in the ecosystem.

Colleen discusses the importance of understanding your assets. If you have live video, your approach is very different to on-demand. If you are lucky enough to have an asset that is getting millions upon millions of views, you’ll want to compress every bit out of that, but for live, there’s a limit to what you can achieve. Also, you need to understand how your long-tail archive is going to be accessed to decide how much effort your business wants to put into compressing the assets further.

The video comes to a close by discussing the Alliance of Open Media’s approach to AV1 encoders and decoders, discussing the hard work optimising the libAV1 research encoder and the other implementations which are ready for production. Colleen points out the benefit of webassembly which allows a full decoder to be pushed into the browser and the discussion ends talking about codec support for HDR delivery technologies such as HDR10+.

Watch now!

Speakers

|

Colleen Henry Cobra Commander of Facebook Video Special Forces. |

|

Anush Moorthy Manager, Video & Imagine Encoding Netflix |

|

Amnon Cohen-Tidhar Senior Director or Video Architecture, Cloudinary |

|

Moderator: Jan Ozer Principal, Stremaing Learning Center Contributing Editor, Streaming Media |