A nuanced look at AV1. If we’ve learnt one thing about codecs over the last year or more, it’s that in the modern world pure bitrate efficiency isn’t the only game in town. JPEG 2000 and, now, JPEG XS, have always been excused their high bitrate compared to MPEG codecs because they deliver low latency and high fidelity. Now, it’s clear that we also need to consider the computational demand of codec when evaluating which to use in any one situation.

John Porterfield welcomes Facebook’s David Ronca to understand how AV1’s arriving on the market. David’s the director of Facebook’s video processing team, so is in pole position to understand how useful AV1 is in delivering video to viewers and how well it achieves its goals. The conversation looks at how to encode, the unexpected ways in which AV1 performs better than other codecs and the state of the hardware and software decoder ecosystem.

David starts by looking at the convex hull, explaining that it’s a way of encoding content multiple times at different resolutions and bitrates and graphing the results. This graph allows you to find the best combination of bitrate and resolution for a target quality. This works well, but the multiple encodes burdens the decision with a lot of extra computation to get the best set of encoding parameters. As proof of its effectiveness, David cites a time when a 200kbps max target was given for and encoder of video plus audio. The convex hull method gave a good experience for small screens despite the compromises made in encoding fidelity. The important part is being flexible on which resolution you choose to encode because by allowing the resolution to drift up or down as well as the bitrate, higher fidelity combinations can be found over keeping the resolution fixed. This is called per-title encoding and was pioneered by Netflix as discussed in the linked talk, where David previously worked and authored this blog post on the topic.

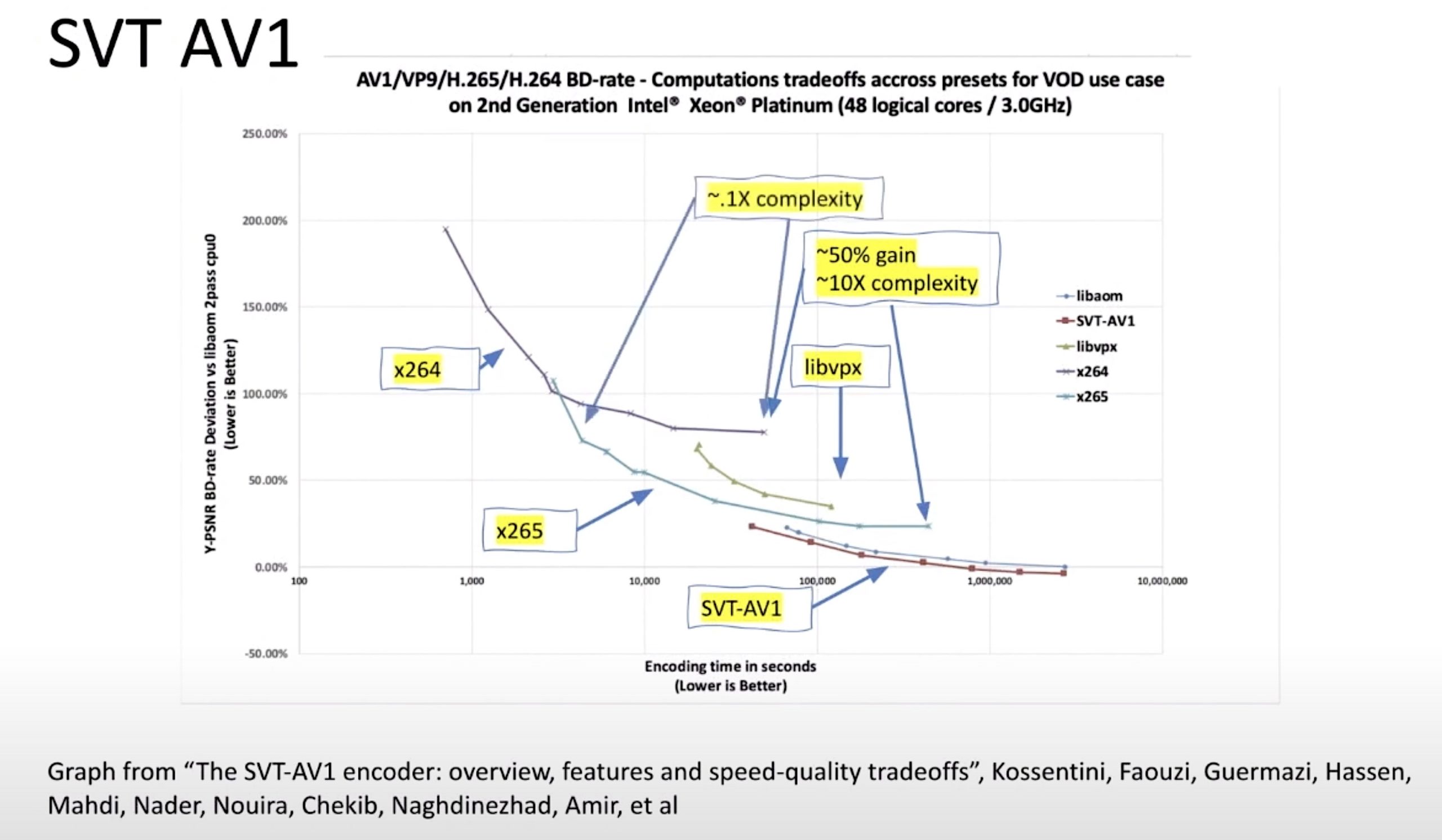

It’s an accepted fact that encoder complexity increases for every generation. Whilst this makes sense, particularly in the standard MPEG line where MPEG 2 gave way to AVC which gave way to HEVC which is now being superseded by VVC all of which achieved an approximately 50% compression improvement at the cost of a ten-fold computation increase. But David contends that this buries the lede. Whilst it’s true that the best (read: slowest) compression improves by 50% and has a 10% complexity increase, it’s often missed that at the other end of the curve, one of the fastest settings of the newer codec can now match the best of the old codec with a 90% reduction in computation. For companies working in the software world encoding, this is big news. David demonstrates this by graphing the SVT-AV1 encoder against the x265 HEVC encoder and that against x264.

David touches on an important point, that there is so much video encoding going on in the tech giants and distributed around the world, that it’s important for us to keep reducing the complexity year on year. As it is now, with the complexity increasing with each generation of encoder, something has to give in the future otherwise complexity will go off the scale. The Alliance for Open Media’s AV1 has something to say on the topic as it’s improved on HEVC with only a 5% increase in complexity. Other codecs such as MPEG’s LCEVC also deliver improved bitrate but at lower complexity. There is a clear environmental impact from video encoding and David is focused on reducing this.

AOM is also fighting the commercial problem that codecs have. Companies don’t mind paying for codecs, but they do mind uncertainty. After all, what’s the point in paying for a codec if you still might be approached for more money. Whilst MPEG’s implementation of VVC and EVC aims to give more control to companies to help them control their risk, AOM’s royalty-free codec with a defence fund against legal attacks, arguably, gives the most predictable risk of all. AOM’s aim, David explains, is to allow the web to expand without having to worry about royalty fees.

Next is some disappointing news for AV1 fans. Hardware decoder deployments have been delayed until 2023/24 which probably means no meaningful mobile penetration until 2026/27. In the meantime the very good dav1d decoder and also gav1 are expected to fill the gap. Already quite fast, the aim is for them to be able to do 720p60 decoding for average android devices by 2024.

Watch now!

Speakers

|

David Ronca Director, Video Encoding, |

|

Freelance Video Webcast Producer and Tech Evangelist JP’sChalkTalks YouTube Channel |