Our ability to work remotely during the pandemic is thanks to the hard work of many people who have developed the technologies which have made it possible. Even before the pandemic struck, this work was still on-going and gaining momentum to overcome more challenges and more hurdles of working in IP both within the broadcast facility and in the cloud.

SMPTE’s Paul Briscoe moderates the discussion surrounding these on-going efforts to make the cloud a better place for broadcasters in this series of presentation from the SMPTE Toronto section. First in the order is Peter Wharton from TAG V.S. talking about ways to innovate workflows to better suit the cloud.

Peter first outlines the challenges of live cloud production, namely keeping latency low, signal quality high and managing the high bandwidths needed at the same time as keeping a handle on the costs. There is an increasing number of cloud-native solutions but how many are truly innovating? Don’t just move workflows into the cloud, advocates Peter, rather take this opportunity to embrace the cloud.

Working with the cloud will be built on new transport interfaces like RIST and SRT using a modular and open architecture. Scalability is the name of the game for ‘the cloud’ but the real trick is in building your workflows and technology so that you can scale during a live event.

There are still obstacles to be overcome. Bandwidth for uncompressed video is one, with typical signals up to 3Gbps uncompressed which then drives very high data transfer costs. The lack of PTP in the cloud makes ST 2110 workflows difficult, similarly the lack of multicast.

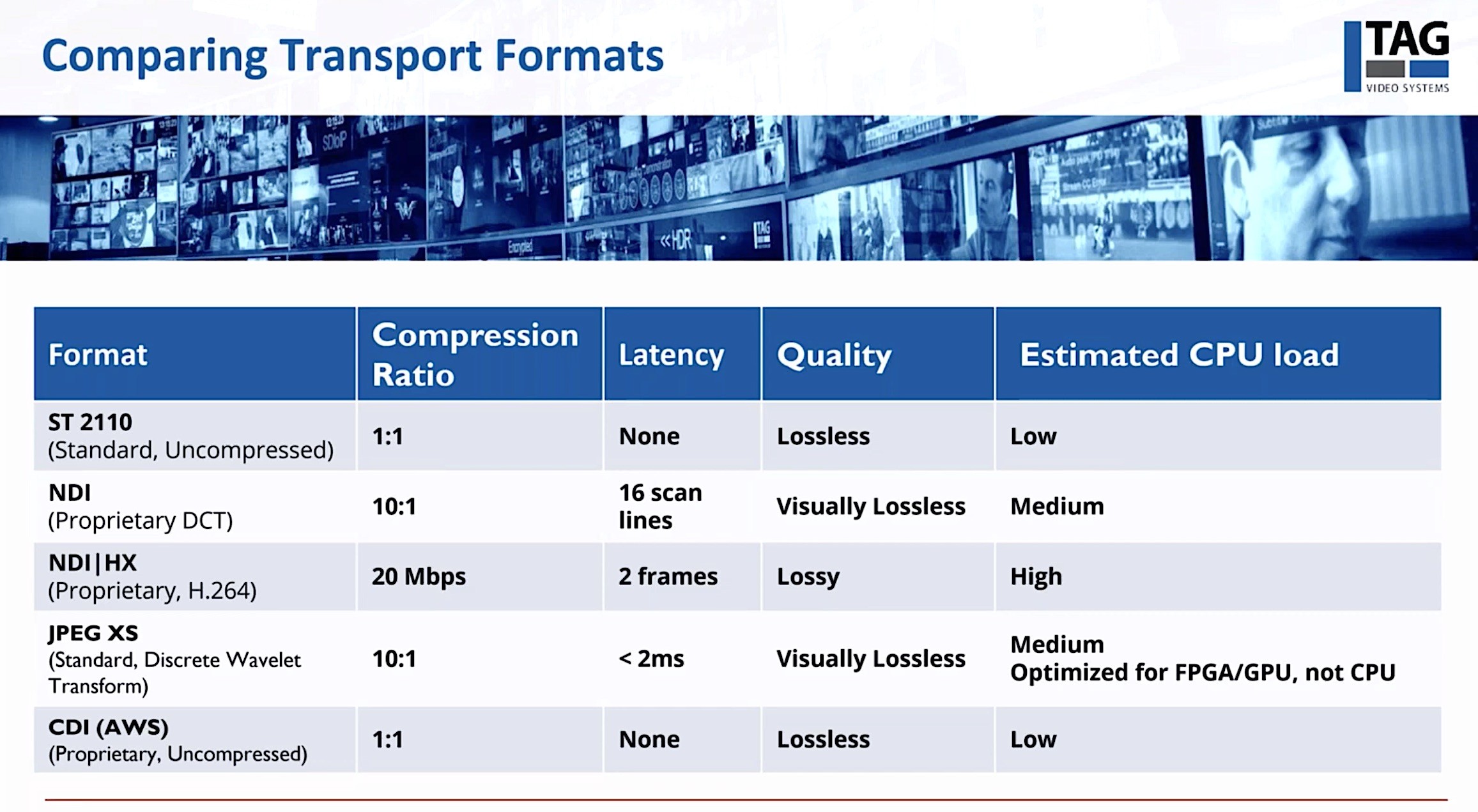

Tackling bandwidth, Peter looks at the low-latency ways to compress video such as NDI, NDI|HX, JPEG XS and Amazon’s lossless CDI. Peter talks us through some of the considerations in choosing the right codec for the task in hand.

Finishing his talk, Peter asks if this isn’t time for a radical change. Why not rethink the entire process and embrace latency? Peter gives an example of a colour grading workflow which has been able to switch from on-prem colour grading on very high-spec computers to running this same, incredibly intensive process in the cloud. The company’s able to spin up thousands of CPUs in the cloud and use spot pricing to create temporary, low cost, extremely powerful computers. This has brought waiting times down for jobs to be processed significantly and has reduced the cost of processing an order of magnitude.

Lastly Peter looks further to the future examining how saturating the stadium with cameras could change the way we operate cameras. With 360-degree coverage of the stadium, the position of the camera can be changed virtually by AI allowing camera operators to be remote from the stadium. There is already work to develop this from Canon and Intel. Whilst this may not be able to replace all camera operators, sports is the home of bleeding-edge technology. How long can it resist the technology to create any camera angle?

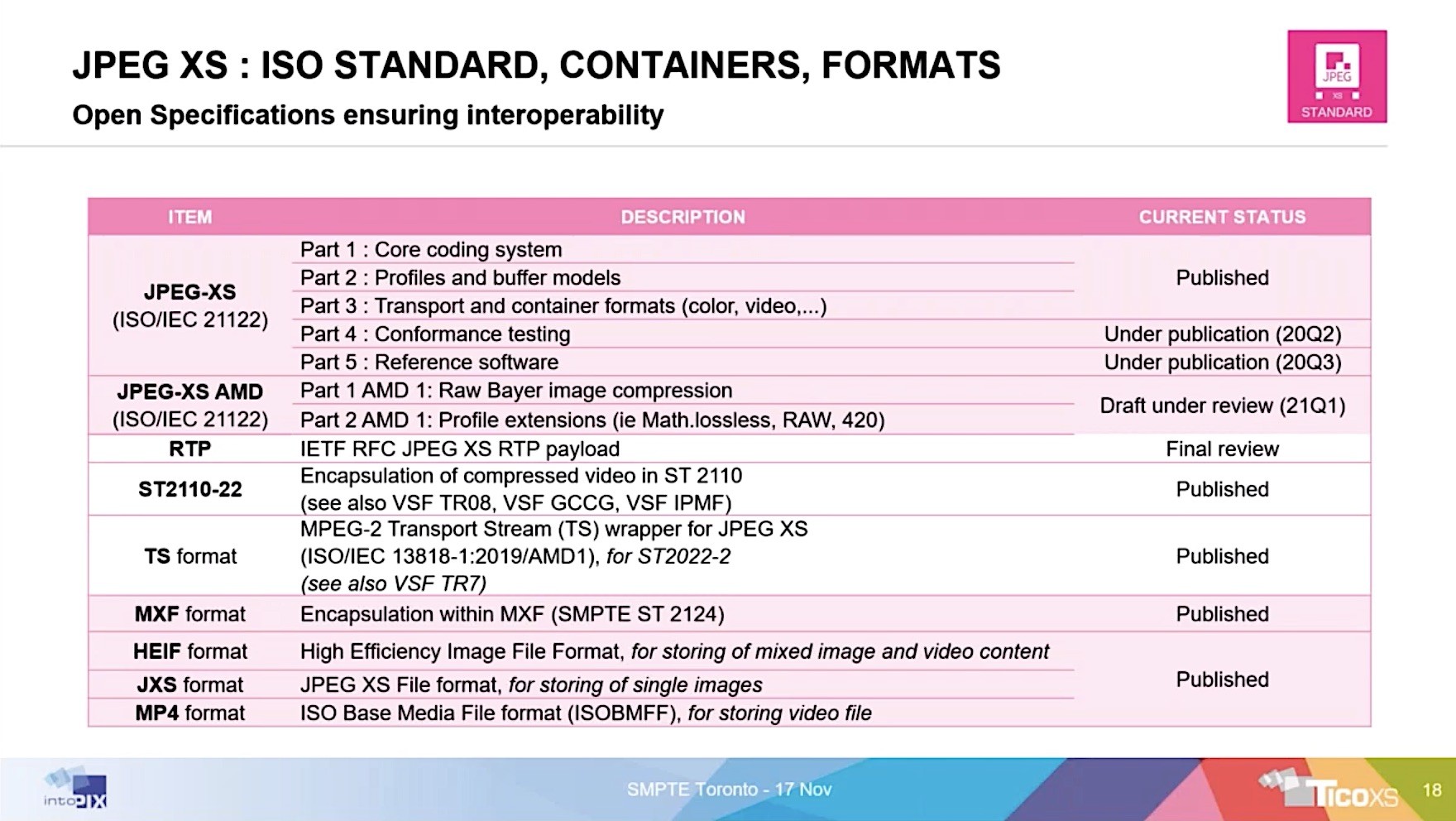

Jean-Baptiste Lorent is next from intoPIX to explain what JPEG XS is. A new, ultra-low-latency, codec it meets the challenges of the industry’s move to IP, its increasing desire to move data rather than people and the continuing trend of COTS servers and cloud infrastructure to be part of the real-time production chain.

As Peter covered, uncompressed data rates are very high. The Tokyo Olympics will be filmed in 8K which racks up close to 80Gbps for 120fps footage. So with JPEG XS standing for Xtra Small and Xtra Speed, it’s no surprise that this new ISO standard is being leant on to help.

Tested as visually lossless to 7 or more encode generations and with latency only a few lines of video, JPEG XS works well in multi-stage live workflows. Jean-Baptiste explains that it’s low complexity and can work well on FPGAs and on CPUs.

JPEG XS can support up to 16-bit values, any chroma and any colour space. It’s been standardised to be carried in MPEG TSes, in SMPTE ST 2110 as 2110-22, over RTP (pending) within HEIF file containers and more. Worst case bitrates are 200Mbps for 1080i, 390Mbps for 1080p60 and 1.4Gbps for 2160p60.

Evolution of Standards-Based IP Workflows Ground-To-Cloud

Last in the presentations is John Mailhot from Imagine Communications and also co-chair of an activity group at the VSF working on standardising interfaces for passing media place to place. Within the data plane, it would be better to avoid vendors repeatedly writing similar drivers. Between ground and cloud, how do we standardise video arriving and the data you need around that. Similarly standardising new technologies like Amazon’s CDI is important.

John outlines the aim of having an interoperability point within the cloud above the low-level data transfer, closer to 7 than to 1 in the OSI model. This work is being done within AIMS, VSF, SMPTE and other organisations based on existing technologies.

Q&A

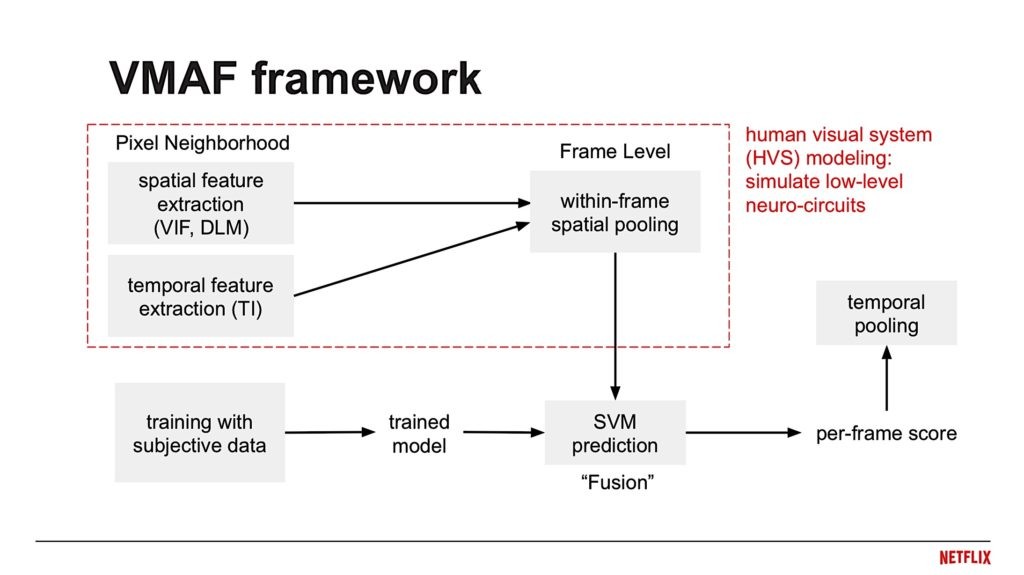

The video finishes with a Q&A and includes comments from AWS’s Evan Statton whose talk on CDI that evening is not part of this video. The questions cover comparing NDI with JPEG XS, how CDI uses networking to achieve high bandwidths and high reliability, the balance between minimising network and minimising CPU depending on workflow, the increasingly agile nature of broadcast infrastructure, the need for PTP in the cloud plus the pros and cons of standards versus specifications.

Watch now!

Speakers

|

Peter Wharton Director Corporate Strategy, TAG V.S. President, Happy Robotz Vice President of Membership, SMPTE |

|

Jean-Baptiste Lorent Director Marketing & Sales, intoPIX |

|

John Mailhot Co-Chair Cloud-Gounrd-Cloud-Ground Activity Group, VSF Directory & NMOS Steering Member, AMWA Systems Architect for IP Convergence, Imagine Communcations |

|

Moderator: Paul Briscoe Canadian Regional Governor, SMPTE Consultant, Televisionary Consulting |

|

Evan Statton Principal Architect, Media & Entertainment Amazon Web Services |