The Codec landscape is a more nuanced place than 5 years ago, but there will always be a place for a traditional Codec that cuts file sizes in half while harnessing recent increases in computation. Enter VVC (Versatile Video Codec) the successor to HEVC, created by MPEG and the ITU by JVET (Joint Video Experts Team), which delivers up to 50% compression improvement by evolving the HEVC toolset and adding new features.

In this video Virginie Drugeon from Panasonic takes us through VVC’s advances, its applications and performance in this IEEE BTS webinar. VVC aims not only to deliver better compression but has an emphasis on delivering at higher resolutions with HDR and as 10-bit video. It also acknowledges that natural video isn’t the only video used nowadays with much more content now including computer games and other computer-generated imagery. To achieve this, VVC has had to up its toolset.

Any codec is comprised of a whole set of tools that carry out different tasks. The amount that each of these tools is used to encode the video is controllable, to some extent, and is what gives rise to the different ‘profiles’, ‘levels’ and ‘tiers’ that are mentioned when dealing with MPEG codecs. These are necessary to allow for lower-powered decoding to be possible. Artificially constraining the capabilities of the encoder gives maximum performance guarantees for both the encoder and decoder which gives manufacturers control over the cost of their software and hardware products. Virginie walks us through many of these tools explaining what’s been improved.

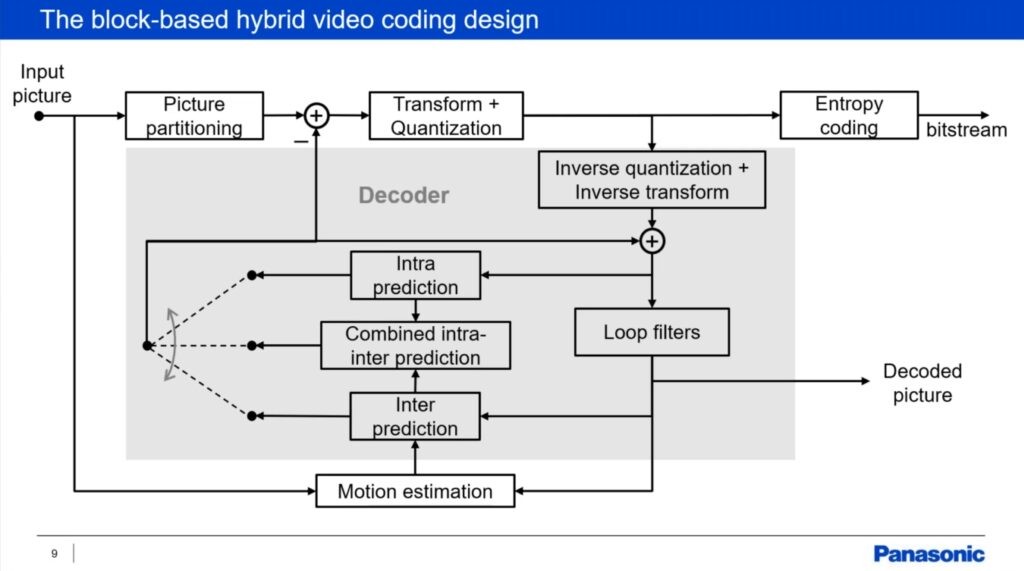

Most codecs split the image up into blocks, not only MPEG codecs but the Chinese AVS codecs and AV1 also do. The more ways you have to do this, the better compression you can achieve but this adds more complexity to the encoding so each generation adds more options to balance compression against the extra computing power now available since the last codec. VVC allows rectangles rather than just squares to be used and the size of sections can now be 128×128 pixels, also covered in this Bitmovin video. This can be done separately for the chroma and luma channels.

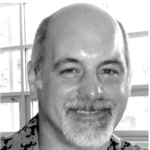

Virginie explains that the encoding is done through predicting the next frame and sending the corrections on top of that. This means that the encoder needs to have a decoder within it so it can see what is decoded and understand the differences. Virginie explains there are three types of prediction. Intra prediction uses the current frame to predict the content of a block, inter prediction which uses other frames to predict video data and also a hybrid mode which uses both, new to VVC. There are now 93 directional intra prediction angles and the introduction of matrix-based intra prediction. This is an example of the beginning of the move to AI for codecs, a move which is seen as inevitable by The Broadcast Knowledge as we see more examples of how traditional mathematical algorithms are improved upon by AI, Machine Learning and/or Deep Learning. A good example of this is super-resolution. In this case, Virginie says that they used machine learning to generate some matrices which are used for the transform meaning that there’s no neural network within the codec, but that the matrices were created based on real-world data. It seems clear that as processing power increases, a neural network will be implemented in future codecs (whether MPEG or otherwise).

For screen encoding, we see that intra block copying (IBC) is still present from HEVC, explained here from 17:30 IBC allows part of a frame to be copied to another which is a great technique for computer-generated content. Whilst this was in HEVC it was not in the basic package of tools in HEVC meaning it was much less accessible as support in the decoders was often lacking. Two new tools are block differential pulse code modulation & transform skip with adapted residual coding each discussed, along with IBC in this free paper.

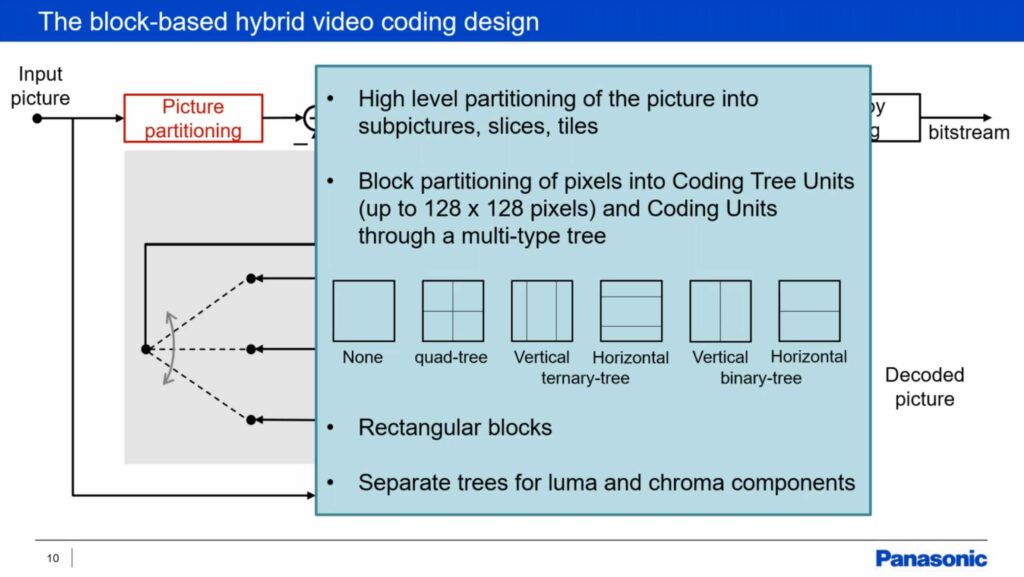

Virginie moves on to Coding performance explaining that the JVET reference software called VTM has been used to compare against HEVC’s HM reference and has shown, using PSNR, an average 41% improvement on luminance with screen content at 48%. Fraunhofer HHI’s VVenc software has been shown to be 49%.

Along with the ability to be applied to screen content and 360-degree video, the versatility in the title of the codec also refers to the different layers and tiers it has which stretch from 4:2:0 10 bit video all the way up to 4:4:4 video including spatial scalability. The main tier is intended for delivery applications and the high for contribution applications with framerates up to 960 fps, up from 300 in HEVC. There are levels defined all the way up to 8K. Virginie spends some time explaining NAL units which are in common with HEVC and AVC, explained here from slide 22 along with the VCL (Video Coding Layer) which Virginie also covers.

Random access has long been essential for linear broadcast video but now also streaming video. This is done with IDR (Instantaneous Decoding Refresh), CRA (Clean Random Access) and GDR (Gradual Decoding Refresh). IDR is well known already, but GDR is a new addition which seeks to smooth out the bitrate. With a traditional IBBPBBPBBI GOP structure, there will be a periodic peak in bitrate because the I frames are much larger than the B and, indeed, P frames. The idea with GDR is to have the I frame gradually transmitted over a number of frames spreading out the peak. This disadvantage is you need to wait longer until you have your full I frame available.

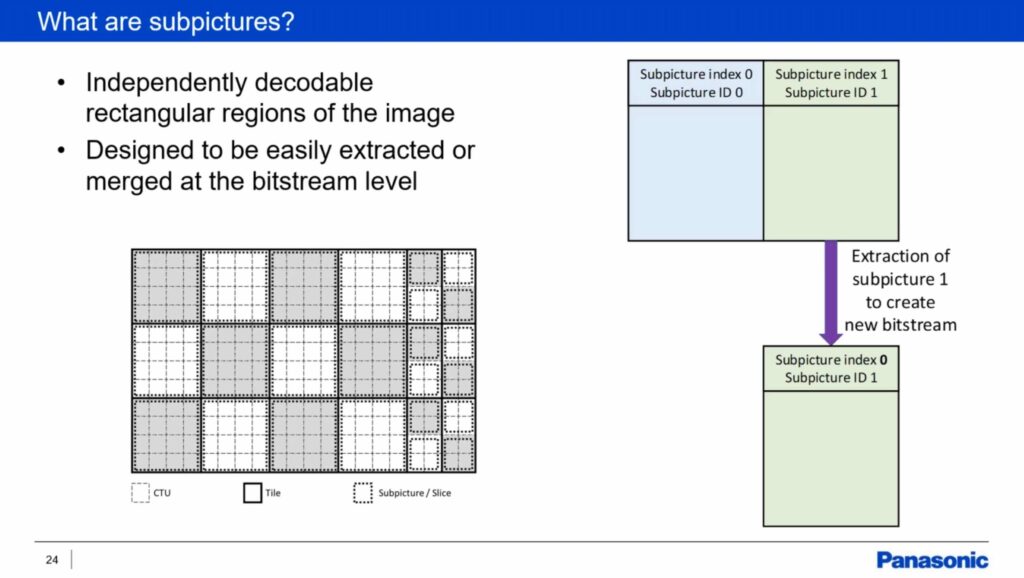

Virginie introduces subpictures which are a major development in VVC allowing separately encoded pictures within the same stream. Effectively creating a multiplexed stream, sections of the picture can be swapped out for other videos. For instance, if you wanted a picture in picture, you could swap the thumbnail video stream before the decoder meaning you only need one decoder for the whole picture. To do the same without VVC, you would need two decoders. Subpictures have found use in 360 video allowing reduced bitrate where only the part which is being watched is shown in high quality. By manipulating the bitstream at the sender end.

Before finishing by explaining that VVC can be carried by both MPEG’s ISO BMFF and MPEG2 Transport Streams, Virginie covers Reference Picture Resampling, also covered in this video from Seattle Video Tech allows reference frames of one resolution to be an I frame for another resolution stream. This has applications in adaptive streaming and spatial scalability. Virginie also covers the enhanced timing available with HRD

Watch now!

Video is free to watch

Speaker

|

Virginie Drugeon Senior Engineer Digital TV Standardisation, Panasonic |