In the last of three sessions on esports, the RTS Thames Valley looks at how vendors for the traditional sports market can adapt and serve this quickly growing market.

Guillaume Neveux from EVS sets the scene talking about the current viewing figures (44 million concurrent peak viewers for League of Legends) and revenue predictions of a 40% increase over the next three years. This is built on sponsorship and, like TV, this takes the form of ad insertion, and programme sponsorship (i.e. logo on screen) to name but two options. Esports has an advantage as they can control the whole world the sport takes place in. This means that advertising signs can be placed, live, on objects in the live stream which are seen by the viewers but not by the players, something which has been attempted in traditional sports but has yet to become common.

Guillaume also looks at how Twitch and YouTube Gaming work, commenting that one of their big differences from traditional sports is the chat room which scrolls next to the game itself. This lends a significant feeling of community to the game which is seldom replicated in traditional sports broadcasting. In general, esports is free to watch. Freemium subscriptions allow you to reduce the number of adverts seen and also improve the chat options.

The next part of the talk spotlights some of the roles unique to esports. The Caster is analogous to a commentator. They are there to weave a story, to explain what’s happening on screen and to add colour to the even by explaining more about what’s happening, about the people and about the game itself. Streamers are individuals who stream themselves playing computer games who, like YouTube personalities, can have extremely large audiences. An Observer is someone who moves around the game world but is invisible to the players, they are analogous to camera operators in that they can control their own view of the world and are also responsible for choosing which views from the players are seen. Essentially they are like a sub vision mixer feeding specific shots into the main programme as well as, in some circumstances, creating dedicated streams of shots for secondary streams. Graphics operators are just as important as in other types of programmes although aspect ratios are all the more tricky and this also involves integration into the game engines.

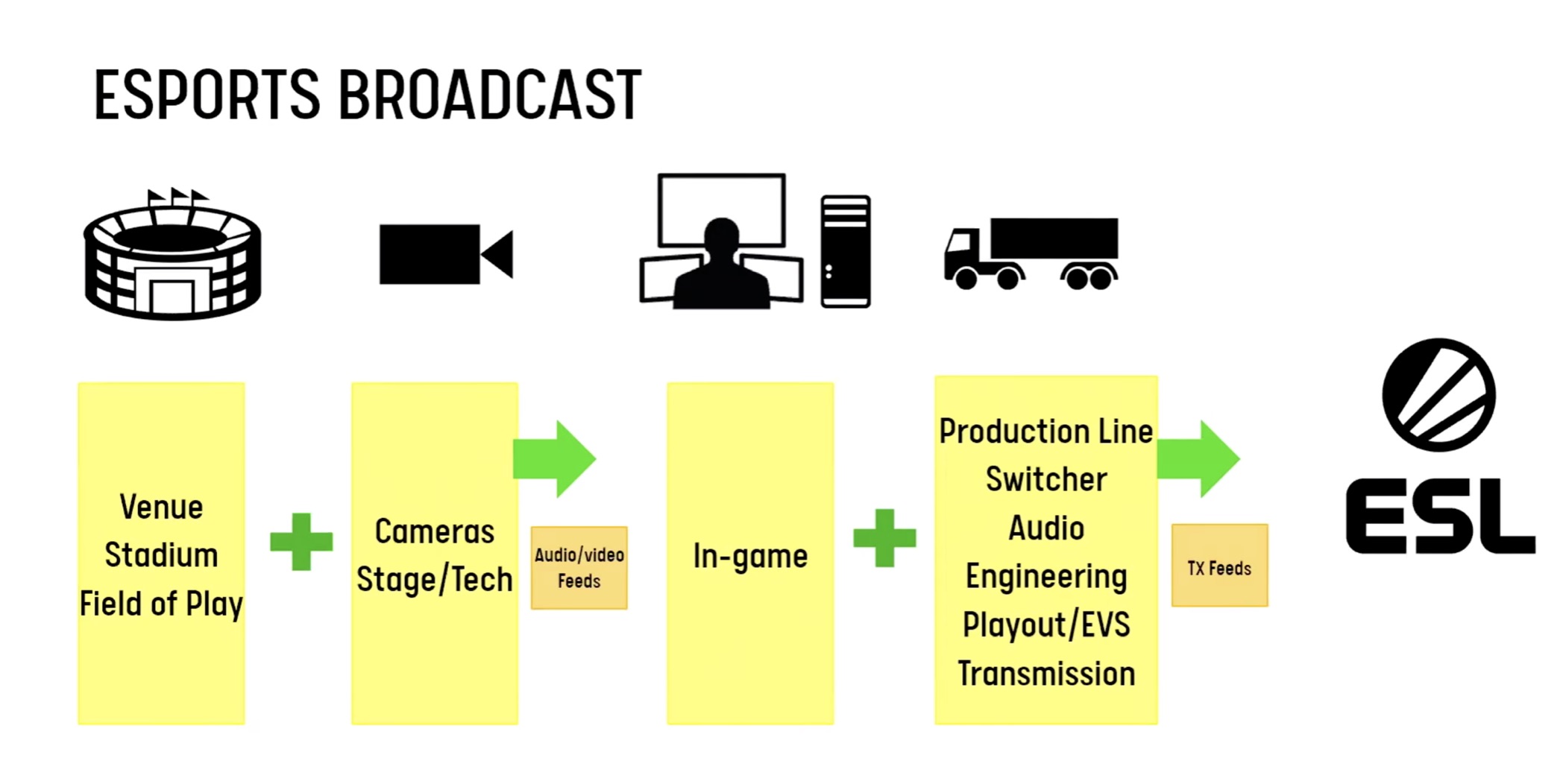

Guillaume also covers the equipment used by esports broadcasters. EVS is a premium brand with products honed to a very specific market. Guillaume explains that although the equipment may seem expensive, the efficiencies derived from buying equipment designed for your workflow a notable compared to creating similar workflows out of other equipment typically due to the added complexity, maintenance and workflow fit. At the end of the day, much of what traditional sports and esports needs is similar – slowmo, replays, graphics insertion – so only some modifications were needed to the EVS products to make them fit into the needed workflows.

Watch now!

Speakers

|

Guillaume Neveux Business Development Manager EMEA, EVS |