There are a number of techniques for achieving low-latency streaming. This talk is one of the few which introduces them in easy to understand ways and then puts them in context briefly showing the manifests or javascript examples of how these would be seen in the wild. Whilst there are plenty of companies who don’t need low-latency streaming, for many it’s a key part of their offering or it’s part of the business model itself. Knowing the techniques in play is to better understand internet streaming in general.

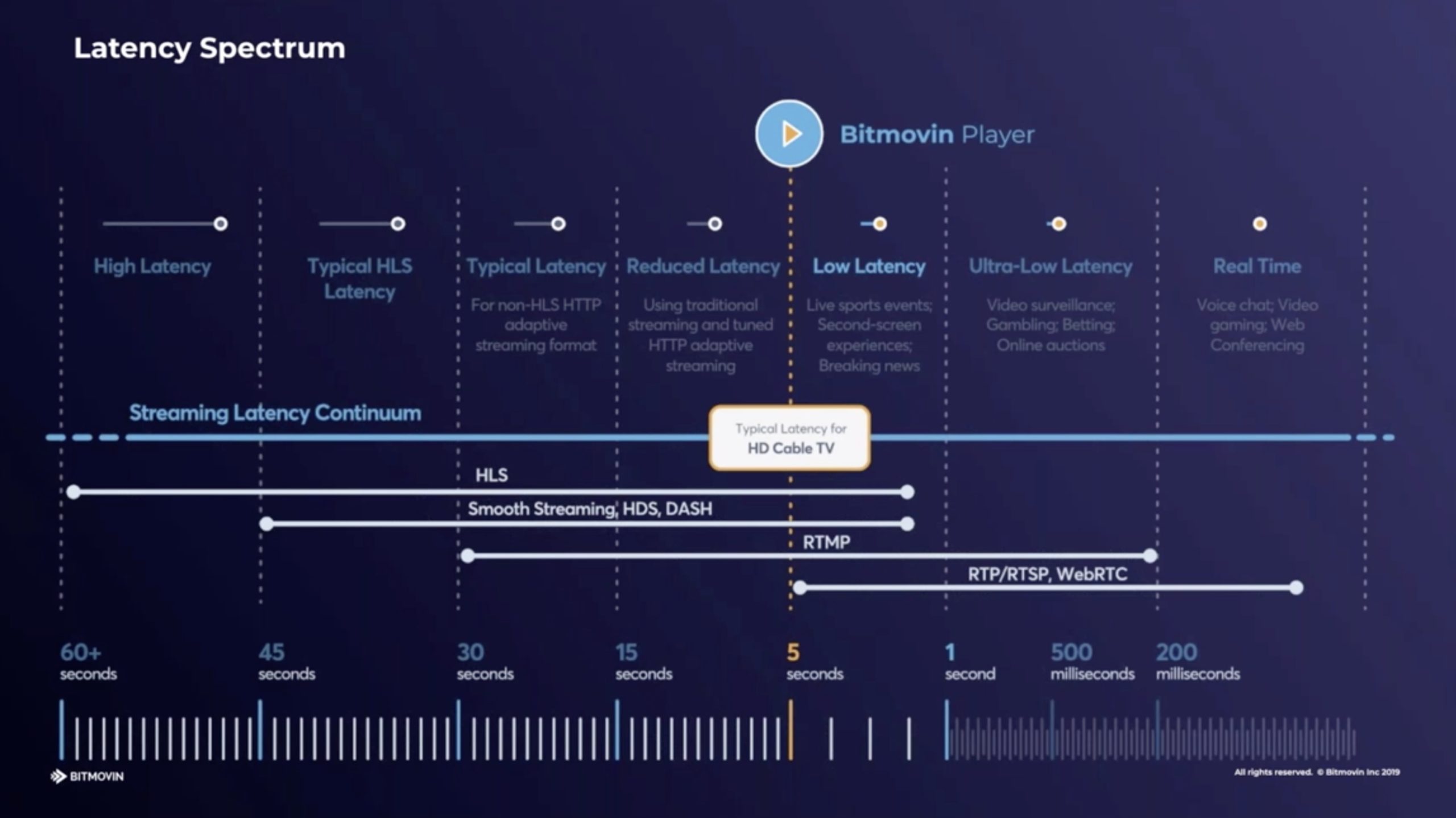

Jameson Steiner from Bitmovin starts by explaining why there is a motivation to cut the latency. One big motivation, aside from the standard live sports examples, is user-generated content like on Twitch where it’s very clear to the streamer, and quite off-putting, when there is large amounts of delay. Whilst delay can be adapted to, the more there is the less interaction is possible. In this situation, it’s the ‘handwaving’ latency that comes in to play. You want the hand on the screen to wave pretty much at the same time as your hand waves in front of the camera. Jameson places different types of distribution on a chart showing latency and we see that low-latency of 5 seconds or less will not only match traditional TV broadcasts, but also work well for live streamers.

Naturally, to fix a problem you need to understand the problem, so Jameson breaks down the legacy methods of delivery to show why the latency exists. The issue comes down to how video is split into sections, say 6 seconds, so that the player downloads a section at a time, reassembles and plays them. Looking from the player’s perspective, if the network suddenly broke or reduced its throughput, it makes sense to have several chunks in reserve. Having three 6-second chunks, a sensible precaution, makes you 18 seconds behind the curve from the off.

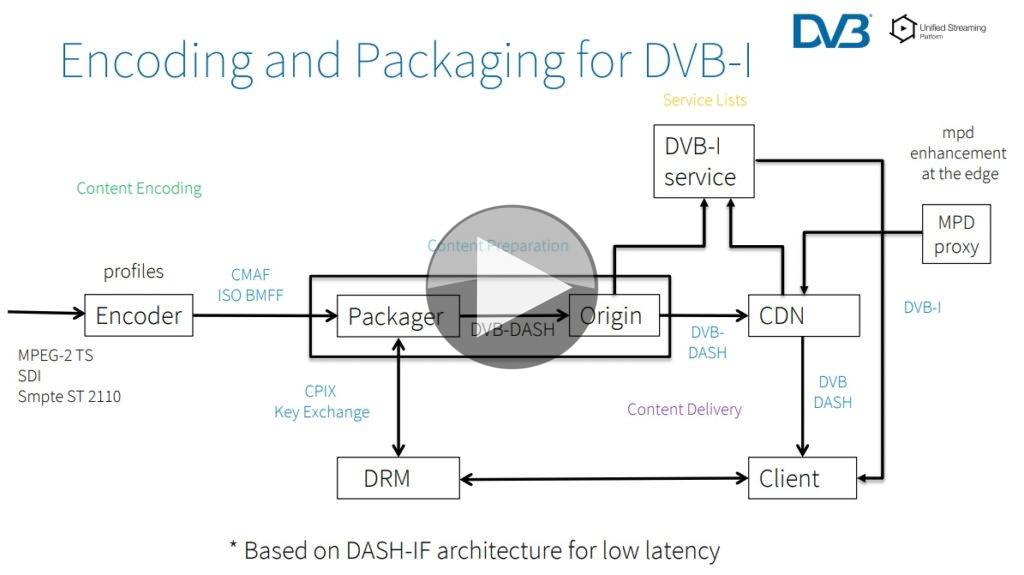

Clearly reducing the segement size is a winner in this scenario. Three 3 second segments will give you just 9 seconds latency; why not go to 1 second? Well encoding inefficiency is one reason. If you reduce the amount of time a temporal codec has of a video, its efficiency will drop and bitrate will increase to maintain quality. Jameson explains the other knock-on effects such as CDN inefficiencies and network requests. The standardised way to avoid these problems is to use CMAF (Common Media Application Format) which is based on MPEG DASH and ISO BMFF. CMAF, and DASH in general, has the benefit of coming from a standards body whose aim was to remove vendor lock-in that may be felt with HLS and was certainly felt with RTMP. Check out MPEG’s short white paper on the topic (zipped .docx file)

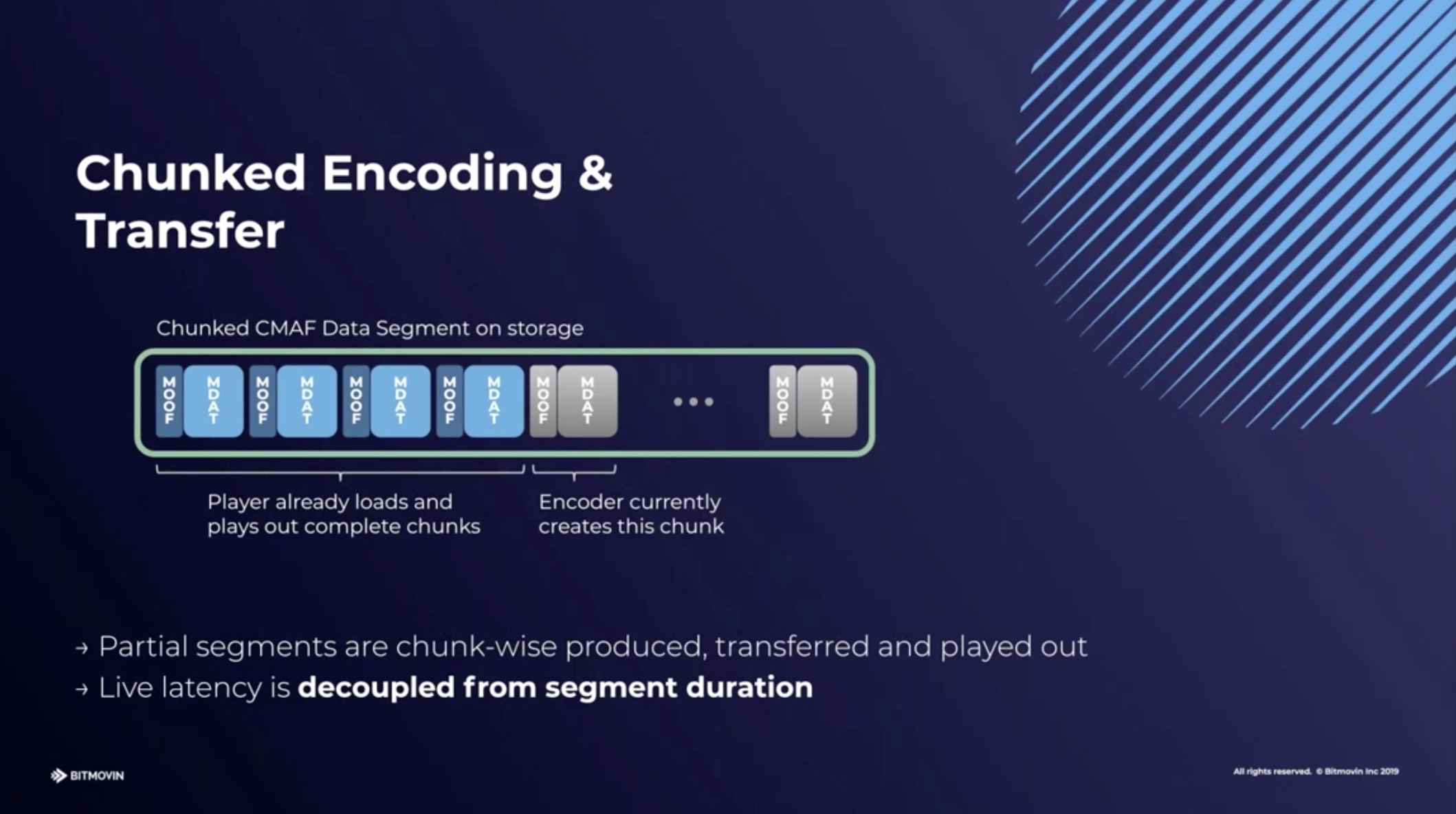

CMAF uses chunked transfer meaning that as the encoder writes the data to the disk, the web server sends it to the client. This is different to the default where a file is only sent after it’s been completely written. This has the effect of the not having to wait up to 6 seconds to a 6-second chunk to start being sent; the download time also needs to be counted. Rather, almost as soon as the chunk has been finished by the encoder, it’s arrived at the destination. This is a feature of HTTP 1.1 and after so is not new, but it still needs to be enabled and considered as part of the delivery.

CMAF goes beyond simple HTTP 1.1 chunked transfer which is a technique used in low-latency HLS, covered later, by creating extra structure within the 6-second segment (until now, called a chunk in this article). This extra structure allows the segment to be downloaded in smaller chunks decoupling the segment length from the player latency. Chunked transfer does cause a notable problem however which has not yet been conclusively solved. Jameson explains how traditionally each large segment typically arrives faster than realtime. By measuring how fast it arrives, given the player knows the duration, it can estimate the bandwidth available at that time on the network. With chunked transfer, as we saw, we are receiving data as it’s being created. By definition, we are now getting it in realtime so there is no opportunity to receive it any quicker. The bandwidth estimation element, as shown the presentation, is used to work out if the player needs to go down or could go up to another stream at a different bitrate – part of standard ABR. So the catastrophe here is the going down in latency has hampered our ability to switch bitrates and whilst the viewer can see the video close to real-time, who’s to say if they are seeing it at the best quality?

Low-Latency HLS/DASH is a way of extending DASH and HLS without using CMAF. Jameson explains some techniques such as advertising segments in advance to allow players to pre-request. It also relies on finding the compromise point of encoding inefficiency vs segment length, typically held to be around 2 seconds, to minimise the latency. At this point we start seeing examples of the techniques in manifests and javascript allowing us to understand how this is actually signalled and implemented.

Apple is on its second major revision of LL-HLS which has responded to many of the initial complaints from the community. Whilst it can use HTTP/2 to help push segments out, this caused problems in practice so it can now preload hints, as Jameson explains in order to remove round-trip times from requests. Jameson looks at the other of Apple’s techniques and shows how they look in manifest files.

The final section looks at problems in implementing these features such as chunks being fragmented across TCP packets, the bandwidth estimation question and dealing with playback speed in order to adjust the players position in time – speed-ups and slow-downs of 5 to 10% can be possible depending on content.

Watch now!

Download the presentation

Speaker

|

Jameson Steiner Software Engineer, Bitmovin |