An evolution from HEVC, VVC is a codec that not only delivers the traditional 50% bit rate reduction over its predecessor but also has specific optimisations for screen content (e.g. computer gaming) and 360-degree video.

Christian Feldmann from Bitmovin explains how VCC manages to deliver this bitrate reduction. Whilst VVC makes no claims to be a totally new codec, Christian explains that the fundamental way the codec works, at a basic level, is the same as all block-based codecs including MPEG 2 and AV1. The bitrate savings come from incremental improvements in technique or embracing a higher computation load to perform one function more thoroughly.

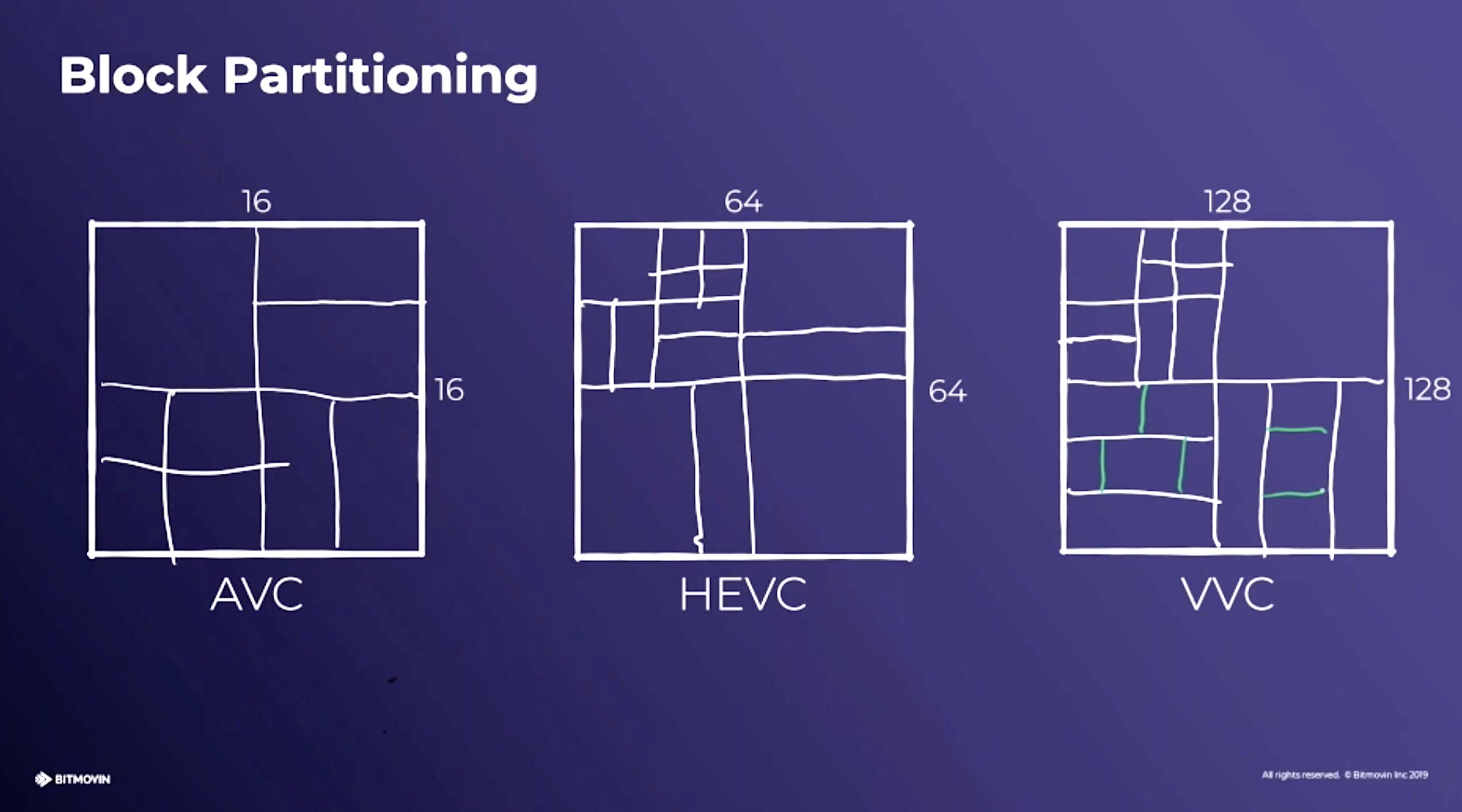

Block partitioning is one good example. Whilst AVC macroblocks are all 16×16 pixels in size, VVC allows 128×128 blocks. For larger areas of ‘solid’ colour, this allows for more efficiency. But the main advance comes in the fact you can sub-divide each of these blocks into different sized rectangles. Whilst sub-dividing has always been possible back to AVC, we have more possible shapes available now allowing the divisions to be created in closer alignment with the video.

Tiles and slices are a way of organising the macroblocks, allowing them to be treated together as a group. This is grouping isn’t taken lightly; each group can be decoded separately. This allows the video to be split into sub-videos. This can be used for multiviewer-style applications or, for instance, to allow multiple 4k decoders to decode a 16k. This could be one of those features which sees lots of innovative use…or, if it’s too complicated/restricted, will see no mainstream take-up.

Christian outlines other techniques such as intra-prediction where macroblocks are predicted from already-decoded macroblocks. Any time a codec can predict a value, this tends to reduce bitrate. Not because it necessarily gets it right, but because it then only needs an error correction, typically a smaller number, to give it the correct value. Similarly, prediction is also possible now between the Y, U and V channels.

Finishing off, Christian hits geometric partitioning, similar to AV1, which allows diagonal splitting of macroblocks with each section having separate motion vectors. He also explains affine motion prediction, allowing blocks to scale, rotate, change aspect ratio and shear. Finally Christian discusses the performance possible from the codec.

To find out more about VVC, including the content-based tuning such as for screen graphics, which is partly where the ‘versatile’ in VVC’s name comes from, listen to this talk, from 19 minutes in, given by Benjamin Bross from Fraunhofer. For Christian’s summary of all this year’s new MPEG codecs, see his previous video in the series.

Watch now!

Free to watch

Speaker

|

Christian Feldmann Team Lead, Encoding Bitmovin |