Work is ongoing in the IPMX project to reduce SMPTE ST 2110’s reliance on PTP, but the reality is that PTP is currently necessary for digital audio systems as well as for most ST 2110 workflows. There are certainly challenges in deploying PTP from an architectural standpoint with some established best practices, but these are only useful when you have the PTP signal itself. For the times when you don’t have a local PTP clock, delivery over a WAN may be your only solution. With PTP’s standards not written with a WAN in mind, can this be done and what are the problems?

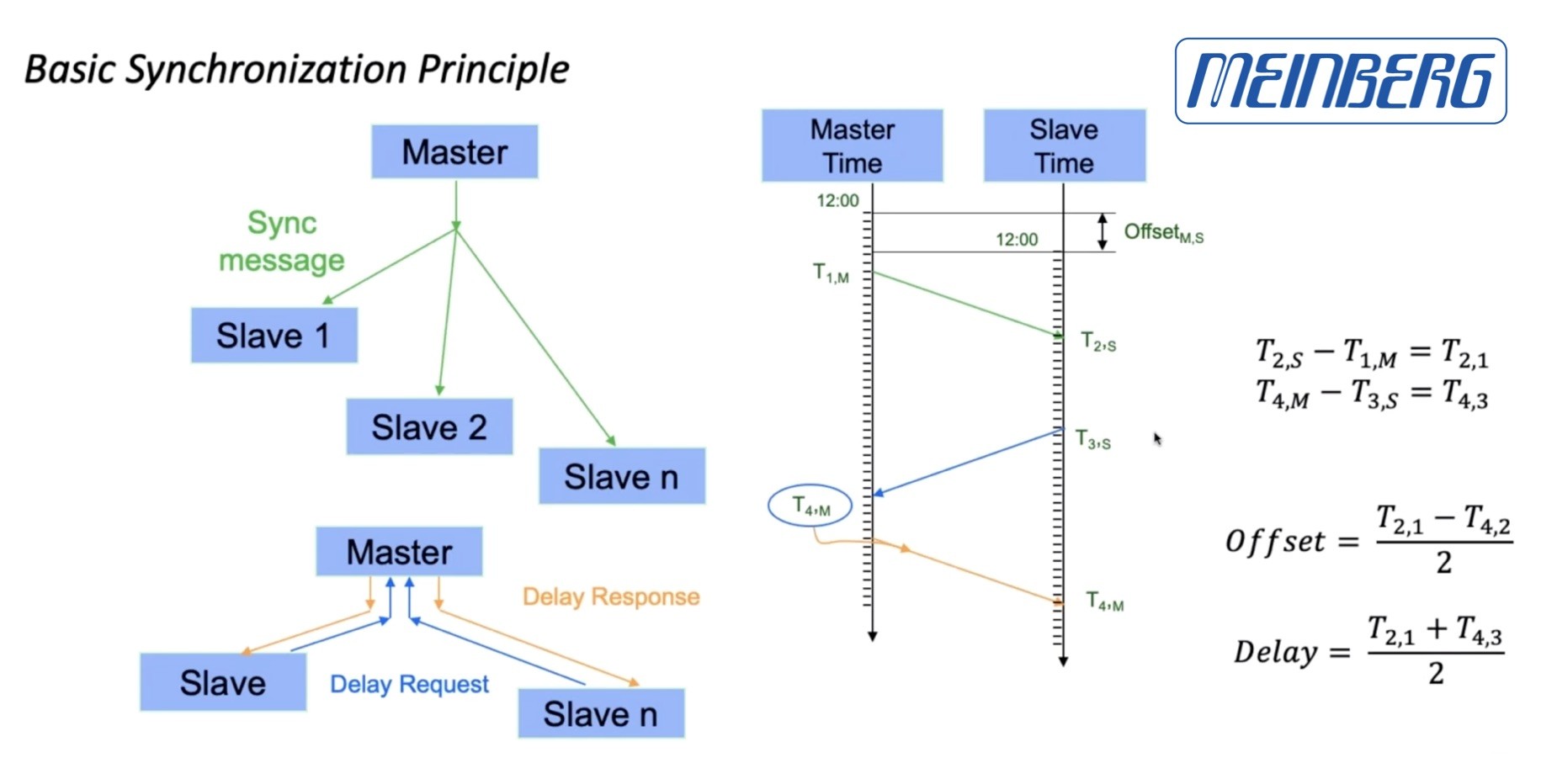

Meinberg’s Daniel Boldt describes the work he’s been involved with in testing PTP delivery over Wide Area Networks (WANs) which are known for having higher, more variable latency than Local Area Networks (LANs) which are usually better managed with low latency which users can interrogate to understand exactly how traffic is moving and configure it to behave as needed. One aspect that Daniel focuses on today is Packet Delay Variation (PDV) which is a term that describes the difference in time between the packets which arrive the soonest and those that arrive last. For accurate timing, we would prefer overall latency to be very low and for each packet to take the same amount of time to arrive. In real networks, this isn’t what happens as there are queuing delays in network equipment depending on how busy the device is both in general and on the specific port being used for the traffic. These delays vary from second to second as well as throughout the day. Asymmetry can develop between send and receive paths meaning packets in one direction take half the time to arrive than those in the other. Finally, path switching can create sudden step changes in path latency.

Boundary Clocks and Transparent Clocks can resolve some of this as they take in to account the delays through switches. Over the internet, however, these just don’t exist so your options are to either build your own WAN using dark fibre or to deal with these problems at the remote site. If you are able to have a clock at the remote site, you could use the local GNSS-locked clock with the WAN as a backup feed to help when GNSS reception isn’t available. But when that’s not possible due to cost, space or inability to rack an antenna, something more clever is needed.

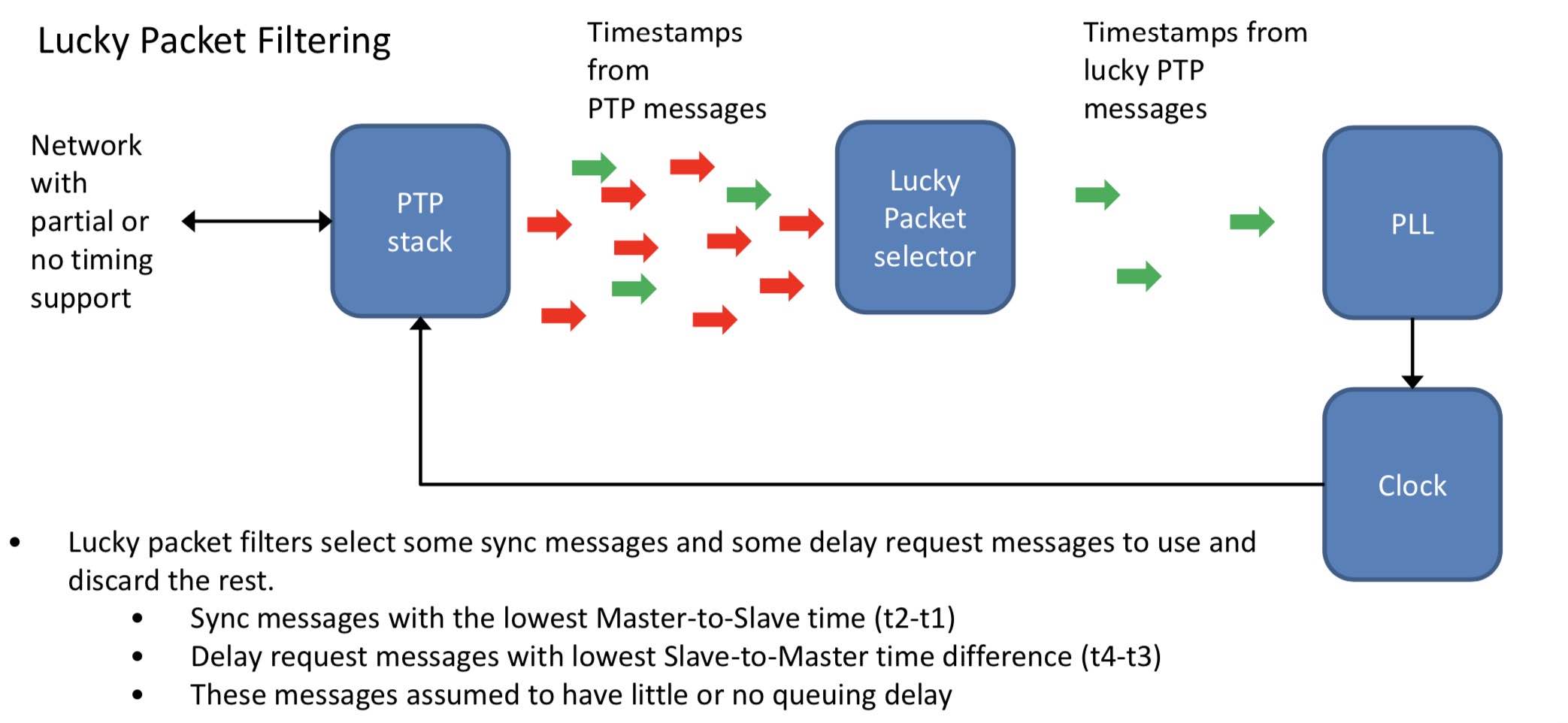

The ‘lucky packet filter’ is a way of cleaning up the timing packets. Typically, PTP timing packets will arrive between 8 and 16 times a second, each one stamped with the time it was sent. When received, its propagation time can be easily calculated and put in a buffer. The filter can look at the statistics then throw away any packets which took a long time to arrive. Effectively this helps select for those packets which had the least interference through the network. Packets which got held a long time are not useful for calculating the typical propagation time of packets so it makes sense to discard them. In a three-day-long test, Meinberg used a higher transmit rate of 64 packets per second saw the filter reduced jitter from 100 microseconds to an offset variation of 5 microseconds. When this was fed into a high-quality clock filter, the final jitter was only 300ns which was well within the 500ns requirement of ST 2059-2 used for SMPTE ST 2110.

Daniel concludes the video by showing the results of a test with WDR where a PTP Slave gateway device was fed with 16 packets a second from a master PTP switch over the WAN. The lucky packet filter produced a timing signal within 500ns and after going through an asymmetry step detection process in the clock produced a signal with an accuracy of no more than 100ns.

Watch now!

Speaker

|

Daniel Boldt Meinberg |