5G seems to offer so much, but there is a lot of nuance under the headlines. Which of the features will telcos actually provide? When will the spectrum become available? How will we cope with the new levels of complexity? Whilst for many 5G will simply ‘work’, when broadcasters look to use it for delivering programming, they need to look a few levels deeper.

In this wide-ranging video from the SMPTE Toronto Section, four speakers take us through the technologies at play and they ways they can be implemented to cut through the hype and help us understand what could actually be achieved, in time, using 5G technology.

Michael J Martin is first up who covers topics such as spectrum use, modulation, types of cells, beam forming and security. Regarding spectrum, Michael explains that 5G uses three frequency bands, the sub 1GHz spectrum that’s been in use for many years, a 3Ghz range and a millimetre range at 26Ghz.

“It’s going to be at least a decade until we get 5G as wonderful as 4G is today.”

Michael highlights a problem faced in upgrading infrastructure to 5G, the amount of towers/sites and engineer availability. It’s simply going to take a long time to upgrade them all even in a small, dense environment. This will deal with the upgrade of existing large sites, but 5G provides also for smaller cells, (micro, pico and femto cells). These small cells are very important in delivering the millimetre wavelength part of the spectrum.

We look at MIMO and beam forming next. MIMO is an important technology as it, effectively, collects reflected versions of the transmitted signals and processes them to create stronger reception. 5G uses MIMO in combination with beam forming where the transmitter itself electronically manipulates the transmitter array to focus the transmission and localise it to a specific receiver/number of receivers.

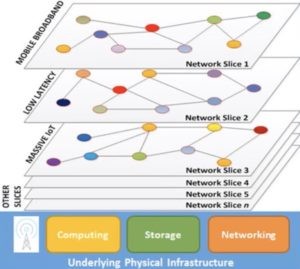

Lastly, Michael talks about Network Slicing which is possibly one of the most anticipated features of 5G by the broadcast community. The idea being that the broadcaster can reserve its own slice of spectrum so when sharing an environment with 30,000 other receivers, they will still have the bandwidth they need.

Our next speaker is Craig Snow from Huawei outlines how secondary networks can be created for companies for private use which, interestingly, partly uses separate frequencies from public network. Network slicing can be used to separate your enterprise 5G network into separate networks fro production, IT support etc. Craig then looks at the whole broadcast chain and shows where 5G can be used and we quickly see that there are many uses in live production as well as in distribution. This can also mean that remote production becomes more practical for some use cases.

Craig moves on to look at physical transmitter options showing a range of sub 1Kg transmitters, many of which have in-built Wi-Fi, and then shows how external microwave backhaul might look for a number of your buildings in a local area connecting back to a central tower.

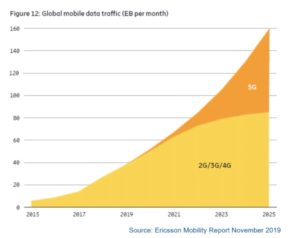

Next is Sayan Sivanathan who works for Bell Mobility and goes in to more detail regarding the wider range of use cases for 5G. Starting by comparing it to 4G, highlighting the increased data rates, improved spectrum efficiency and connection density of devices, he paints a rosy picture of the future. All of these factors support use cases such as remote control and telemetry from automated vehicles (whether in industrial or public settings.) Sayan then looks at the deployment status in the US, Europe and Korea. He shows the timeline for spectrum auction in Canada, talks through photos of 5G transmitters in the real world.

Finishing off today’s session is Tony Jones from MediaKind who focuses in on which 5G features are going to be useful for Media and Entertainment. One is ‘better video on mobile’. Tony picks up on a topic mentioned by Michael at the beginning of the video: processing at the edge. Edge processing, meaning having compute power at the closest point of the network to your end user allows you to deliver customised manifest and deal with rights management with minimal latency.

Tony explains how MediaKind worked with Intel and Ericsson to deliver 5G remote production for the 2018 US Open. 5G is often seen as a great way to make covering golf cheaper, more aesthetically pleasing and also quicker to rig.

The session ends with a Q&A

Watch now!

Speakers

|

Michael J Martin MICAN Communications Blog: vividcomm.com |

|

Tony Jones Principal Technologist MediaKind Global |

|

Craig Snow Enterprise Accounts Director, Huawei |

|

Sayan Sivanathan Senior Manager – IoT, Smart Cities & 5G Business Development Bell Mobility |