Audio has a long heritage in IP compared to video, so there’s plenty of overlap and there are edge cases abound when working between RAVENNA, AES67 and SMPTE ST 2110-30 and -31. SMPTE’s 2110 suite of standards currently holds two methods of carrying audio including a way of carrying encoded audio such as Dolby AC4 and Dolby E.

RAVENNA Evangelist Andreas Hildebrand is joined by Dolby Labs architect James Cowdrey to discuss the compatibility of -30 and -31 with AES67 and how non-PCM data can be carried in -31 whether that be lightly compressed audio, object audio for immersive experiences or even just pure metadata.

Andreas starts by revising the key differences between AES67 and RAVENNA. The core of AES67 fits neatly within RAVENNA’s capabilities including the transport of up to 24-bit linear PCM with 48 samples per packet and up to 8 channels of 48kHz audio. RAVENNA offers more sample rates, more channels and adds discovery and redundancy with modes such as ‘MADI’ and ‘High performance’ which help constrain and select the relevant parameters.

SMPTE ST 2110-30 is based on AES67 but adds its own constraints such that any -30 stream can be received by an AES67 decoder, however, an AES67 sender needs to be aware of -30’s constraints for it to be correctly decoded by a -30 receiver. Andreas says that all AES67 senders now have this capability.

Source: ALC NetworX

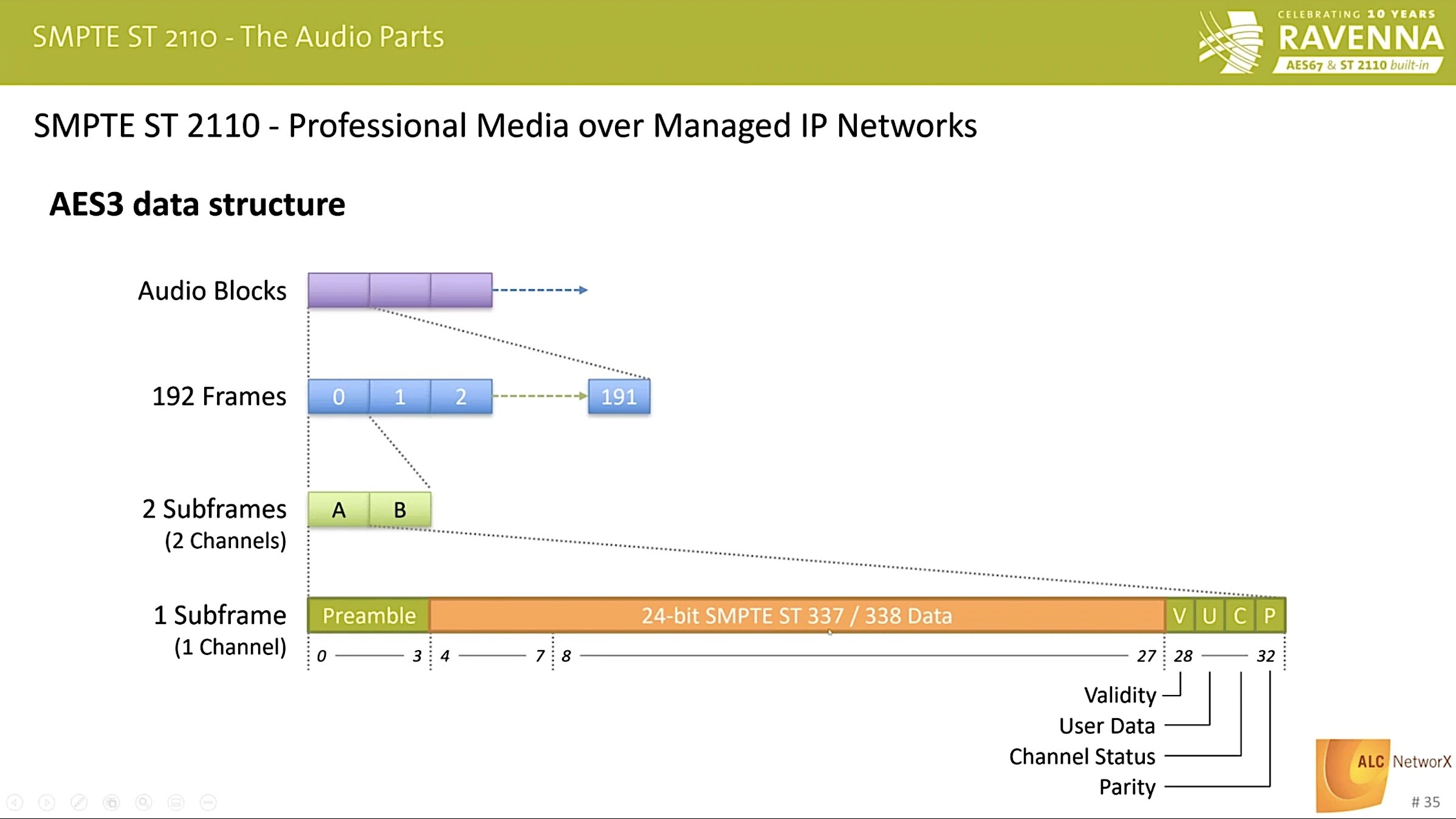

In contrast to 2110-30, 2110-31 is all about AES3 and the ability of AES3 to carry both linear PCM and non-PCM data. We look at the structure of the AES3 which contains audio blocks each of which has 192 Frames. These frames are split into 2, in the case of stereo, 64 in the case of MADI. Within each of these subframes, we finally find the preamble and the 24-bit data. Andreas explains how this is linked to AM824 and the SDP details needed.

James Cowdery leads the second part of today’s talk first talking about SMPTE ST 337 which details how to send non-PCM audio and data in an AES3 serial digital audio interface. It can carry AC-3, AC-4 for object audio delivering immersive audio experiences, Dolby E and also the metadata standards KLV and Serial ADM.

‘Why use Dolby E?’ asks James. Dolby E has a number of advantages although as bandwidth has become more available, it is increasingly replaced by uncompressed audio. However legacy workflows may now be reliant on IP infrastructure between the receiver and decoder, so it’s important to be able to carry it. Dolby E also packs a whole set of surround sound within a single data stream removing any problems of relative phase and can be carried over MPEG-2 transport streams so it still has plenty of flexibility and uses cases.

Its strength can bring fragility and one way which you can destroy a Dolby E feed is by switching between two videos containing Dolby E in the middle of the data rather than waiting for the gap between packets which is called the guardband. Dolby E needs to be aligned to the video so that you can crossfade and switch between videos without breaking the audio. James makes the point that one reason to use -31 and not -30 to carry Dolby E, or any other non-PCM data, is that -30 assumes that a sample rate converter can be used and so there is usually little control over when an SRC is brought in to use. A sample rate converter, of course, would destroy any non-PCM data.

RAVENNA 824 and 2110-31 gateways will preserver the line position of Dolby data. Can support Dolby E transport can therefore be supported by a vendor without Dolby support. James notes that your Dolby E packets need to be 125 microseconds to achieve packet-level switching without missing a guardband and corrupting data.

Immersive audio requires metadata. sADM is an open specification for metadata interchange, the aim of which is to help interoperability between vendors. sADM metadata can be embedded in SDI, transported uncompressed as SMPTE 302 in MPEG-2 Transport Streams and for 2110, is carried in -31. It’s based on XML description of metadata from the Audio Definition Model and James advises using the GZip compression mode to reduce the bitrate as it can be sent per-frame. An alternative metadata standard is SMPTE ST 336 which is an open format providing a binary payload which makes it a lower-latency method for sending Metadata. These methods of sending metadata made sense in the past, but now, with SMPTE ST 2110 having its own section for metadata essences, we see 2110-41 taking shape to allow data like this to be carried on its own.

Watch now!

Speakers

|

James Cowdery Senior Staff Architect Dolby Laboratories |

|

Andreas Hildebrand RAVENNA Evangelist, ALC NetworX |